Horror Fiction

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Stephen King articles

Shirley Jackson

BIBLIOGRAPHIES

Fontana's "Great Ghost Stories" Series

RELATED CONTENT

Shirley Jackson

House and Guardians

by Kyla Ward

First Appeared in Tabula Rasa#7, 1995

I took my coffee into the dining room and settled down with the morning paper. A woman in New York had had twins in a taxi. A woman in Ohio had just had her seventeenth child. A twelve-year-old girl in Mexico had given birth to a thirteen-pound boy. The lead article on the woman's page was about how to adjust the older child to the new baby. I finally found an account of an axe murder on page seventeen, and held my coffee cup up to my face to see if the steam might revive me.Life Among the Savages

Shirley Jackson, 1953

The Sundial, Ace Books, 1958 |

It is a mark of just what sort of acceptance she had that her short stories such as After You, My Dear Alphonse, George, and of course, The Lottery, appear in English texts and school anthologies to this day. Traditionally a horrible fate for a story; amongst all the bits and pieces I read it was these I remembered, and to my utter surprise recognised as I began to work through the other writings of the author of The Haunting of Hill House. Ms Jackson's short fiction was usually published in the like of The New Yorker, who at this time was also the home of the 'Chas' Addams cartoons; Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post and Harpers Bazaar. After You, My Dear Alphonse, was her first piece, printed by The New Yorker in 1943.

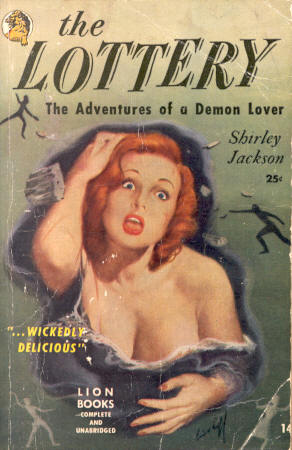

Her first novel, The Road Through the Wall, followed in 1948. But it was with the publication of The Lottery in The New Yorker in August that year, that she began to gain her reputation.

For those who have not encountered The Lottery, ("The people of the village began to gather in the square, between the post office and the bank, around ten o'clock" -- remember?), I refuse to give it away. Suffice to say that it is about a lottery and isolated country town of the type we all know exists, and have usually driven through with an uneasy feeling about what would happen if the car broke down. The New Yorker was besieged with letters for weeks afterwards, some protesting about the 'violent' and pointless story, some praising the brilliant moral allegory, but most demanding to know what it meant. When Joseph Henry Jackson, the literary editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, confessed that he was 'stumped', Jackson wrote to him saying, "I suppose I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village, to shock the story's readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in their own lives." (San Francisco Chronicle, July 22, 1948). In a brief personal sketch produced for Twentieth Century Authors (ed. Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Harcraft, 1954), she states 'I very much dislike writing about myself or my work, and when pressed for autobiographical material can only give a bare chronological outline which contains, naturally, no pertinent facts.' In deference, I will quote the remainder of her description, and with the exception of adding she graduated with a BA from Syracuse University in 1940, leave it at that.

I was born in San Francisco in 1919 and spent most of my early life in California. I was married in 1940 to Stanley Edgar Hyman, critic and numismatist, and we live in Vermont, in a quiet rural community with fine scenery and comfortably far away from city life. Our major exports are books and children, both of which we produce in abundance. The children are Laurence, Joanne, Sarah and Carry: my books include three novels, The Road Through The Wall, Hangsaman, The Bird's Nest, and a collection of short stories, The Lottery. Life Among the Savages is a disrespectful memoir of my children.Her first short fiction collection, The Lottery, or, The Adventures of James Harris, Daemon Lover, was published the next year, and dramatic adaptations followed shortly thereafter. The radio play by Ernest Kinroy was broadcast March 14, 1951, as an episode of the anthology series NBC Presents: Short Story. Ellen M. Violett wrote the first television adaptation, also for NBC, as an episode of Cameo Theatre.

Her next two novels, in 1951 and '54, were Hangsaman and The Bird's Nest. Hangsaman was described as both a superbly realistic evocation of contemporary college life, and a haunting, tenebrous ghost story 'on the invisible shadow-line between fantasy and verisimilitude'. At this point, it might be timely to consider these critiques from The New York Times Review;

This review of Shirley Jackson's new novel properly begins with the confession that I am not sure of anything about it except its almost unflagging interest.Ms Jackson also received rave reviews for her 'disrespectful memoir of my children', and its sequel, Raising Demons (1957). These were surer ground; it was easy to say what they were about and appreciate the 'warm, funny domesticity'. Not all of her 'shorts' were genre; that is what makes reading through The Lottery as a book so unsettling; there is no way to tell whether a particular story will be pure social commentary, like Alphonse, or will go over the edge into that other world, such as the actual The Daemon Lover or the 'witch' story Trial By Combat. It isn't often a horror writer can get away with producing children's books, but she did, including a requested addition to the non-fiction children's series 'Landmark' -- on the Salem witch trials. A description of the book speaks of her 'illuminating' introductory history of the devil.The Haunting of Hill House, 1959I have always felt that some writers should be read and never reviewed. Their talent is haunting and oblique; their mastery of the craft seems complete… And now, Miss Jackson has made it even more difficult for a reviewer to seem pertinent; all he can do is bestow praise.We Have Always Lived in the Castle, 1962

Ms Jackson was often described as a New England witch. It made wonderful copy to say she wrote with a broomstick for a pen, kept six black cats and believed she had caused the accident of an enemy by making a wax image of him with a broken leg. That story was told in her obituary by a friend, the critic Brendan Gill. But for the books, it were perhaps better to call her a sorcerer, because sorcery is the process of manipulating a person's beliefs.

The Lottery, Lion Books, 1950 |

"I have my dolls house… And all the little dolls. One of them, " Fancy giggled, "Is lying in the little bathtub with the water really running. They're little dolls house dolls. They fit exactly into the chairs and the beds. They have little dishes. When I put them to bed they have to go to bed. When my grandmother dies all this is going to belong to me."The next year was published The Haunting of Hill House."And where would we be then?" Essex asked softly, "Fancy?"

Fancy smiled at him. "When my grandmother dies," she said, "I am going to smash my dolls house. I won't need it any more."

There is a story that Shirley Jackson researched The Haunting of Hill House in a very direct way. The most important critical study of Ms Jackson is Shirley Jackson by Lenemaja Friedman (1975), which contains the report that she came across a book on the nineteenth century investigation of a house in England -- Doctor Montague in the novel has the same inspiration. So, she went out to find a haunted house. Sure enough, she found one with "the same air of disease and decay, and if ever a house looked like a candidate for a ghost, it was this one." She investigated the background of the house, and came up with a rather startling fact. It had been built by her great grandfather. Yet more copy for 'the New England witch' The Sundial is definitely set somewhere within reach of Massachusetts; Hill House, by its sheer nature and America's mythological map, is always assumed.

To say Shirley Jackson is a psychological novelist, and that the horror in her stories comes from the increasingly skewed perceptions of her protagonists, fails to suggest the sheer power these vision have. Shirley Jackson manipulates people's beliefs. There are no real things and illusory things. To quote The Sundial; "And anyway, that world isn't any more real than this one." The atmosphere is overwhelming. Hill House was thus perhaps unwisely adapted into the movie The Haunting, by Robert Wise in 1963 (MGM), though by most reports he got away with it.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle was published in 1963. You could say this was another investigation. If we know Shirley Jackson's little village, we also know her old, New England houses. They are the ones you see standing oddly exposed on a hill, outside the town, or the ornate gate and driveway leading off out of sight, proclaiming that someone lives here. There is always a story going round about the broken down old mansion somewhere in the area, how the local vandals have got in, how it should be preserved and 'someone' should investigate. Shirley Jackson's protagonists are the ones who go in. And these investigations may have a wider implication, or take them further than they suppose. One of the more humorous stories in The Lottery is Colloquy, in which a woman consults a doctor because she doesn't understand.

"When I was a little girl I used to live in a world where a lot of other people lived too and they all lived together and things went along like that with no fuss… Look", she said, "Did there used to be words like psychosomatic medicine? Or international cartels? Or bureaucratic centralisation?"We Have Always Lived in the Castle has a twist, but one perfectly in keeping with the slow investigation of her protagonist -- and take that any way you will. This is the one I wish had encountered while I was at school, I suspect the impact of eighteen-year-old 'Merricat' and what happened to the house would have been devastating. Castle was produced as a stage performance by H. Wheeler in 1966, and this may possibly have worked.

Shirley Jackson's final novel, Come Along With Me, was unfinished at the time of her heart attack in 1965. The protagonist is a forty-five year-old New England woman making an investigation of the occult, and yet again, parallels were drawn. It was released by her husband with her yet uncollected stories, including Louisia, Please, for which she had won the Edgar Allen Poe Award in 1961. He edited another selection, The Magic of Shirley Jackson, in 1966.

In her obituary, she is described as 'a neat and cosy woman whose blue eyes looked at the world through light horn-rimmed spectacles'. It states that she only wrote after she had completed the household chores, looking after her children and husband. At the same time, she is being referred to as 'Miss Jackson', and this is perhaps one of the most telling indicators of her achievement and perhaps of her peculiar situation. In the same issues of the New York Times that carry her book reviews, the Women's Pages are made up of reports of socialite weddings, where the women are shown in their bridal gowns as 'Mrs Matthew Reynolds, formerly Ellen Halin'. She was a New England Witch, but still a 'nice', ordinary woman; an author to whom the critics could offer only praise, but really a dutiful wife and mother. This is why I prefer to leave her biographical stats to herself, for finding the right image for Ms Jackson clearly baffled everyone who wrote about her. And when someone has so kindly provided two books describing the high points of her family life, it would seem ungracious to make any pronouncements.

The most recent reprints of her most famous novels have been Penguin editions in 1982, and inclusion in the Robinson Dark Fantasy series in 1987. How the recent rush of gothic anthologies could have missed Jackson, I've no idea, but The Beautiful Stranger, also from Come Along With Me, was included in The Dark Descent: A Fabulous, Formless Darkness, (ed. David G. Hartwell, 1991). As the sole purpose of this article is to encourage you to hunt them down, I can think of no better way than to quote the opening of Hill House;

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.And here, of We Have Always Lived in the Castle;

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in our family is dead.I can only add for the first, not any more, and for the second, she is. Quite definitely content.

Bibliography

- The Road Through the Wall, 1948 (aka. The Other Side of the Street)

- The Lottery, or, The Adventures of James Harris, 1949

- The Lottery, 1950 (screenplay)

- Hangsaman, 1951

- Life Among the Savages, 1953

- The Bird's Nest, 1954 (aka. Lizzie)

- The Witchcraft of Salem Village, 1956 (J)

- Raising Demons, 1957

- The Sundial, 1958

- The Haunting of Hill House, 1959

- The Bad Children: A Play in One Act for Bad Children, 1959

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle, 1962

- Nine Magic Wishes, 1963 (J)

- Famous Sally, 1966 (J, post.)

- Come Along With Me: Part of a Novel, Sixteen Stories and Three Lectures, 1968 (post.)

©2014 Go to top