Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

Cameron Rogers

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Of Angels and Gunslingers

An interview with Cameron Rogers

by David Carroll, 2001

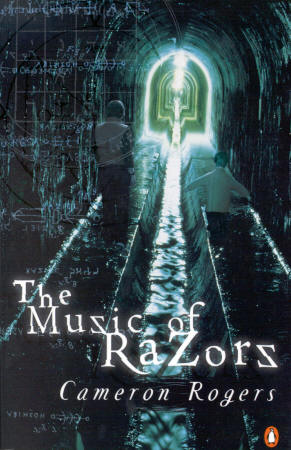

Although his name has appeared on one or two titles in the last couple of years, Cameron Rogers' The Music of Razors has been an unexpected and welcome addition to bookshelves recently. It is a fascinating and assured work of modern fantasy, with a very dark edge to it. It also seems to have had good support from its publisher, Penguin, with excellent design and some heavy names (including Neil Gaiman and Storm Constantine) lending their support to it. Here I talk to Cameron about the book, what has lead up to it, and what's coming next.

Tabula Rasa: Who is Cameron Rogers? And why?

Cameron Rogers: I started writing for myself when I was very young -- seeing Star Wars was what started it. Like a lot of people who wind up writing for a living, it was probably a choice between doing this or climbing a water tower with a rifle. I grew up in Cairns during the Seventies, so escaping into my head was pretty much inevitable.

TR: Tell us a little about The Music of Razors, and its inspiration.

CR: It was a combination of seeing the cover to The Fields of the Nephilim's album Dawnrazor (the title of which has nothing to do with my title for the book) and a piece of art by a guy named Brom. The Brom piece was a painting of a cadaverous gunslinger -- an elegant-yet-corpulent guy in a coat and hat with two big old Cavalry revolvers. When I saw the Nephilim cover the idea for Henry pretty much fell straight into my head, and the Brom painting somehow helped smooth the rough edges off the idea. So I had a two-hundred-year-old "bullet removal specialist" in my head, and then tried working out what to do with him.

Henry first appeared in a standalone 5,000 word novella I wrote for Lothian's After Dark series. They never got back to me on it, and four years later that unaccepted story became the seed for The Music of Razors. I wrote a collection of 3 or 4 short stories centred around Henry and a few other characters, then cut them all together into one cohesive story that mapped the lives of Walter, Hope and Suni from a very young age right up to late adolescence, and follows how their lives are changed by the peripheral interference of Henry and his desire to get out of a deal he'd made with a stricken and banished angel two hundred years ago. So, in that sense, the story is a metaphor for growing up, stepping away from childhood and becoming someone else. It also raises questions about the validity of the shame you sometimes feel about yourself, and the things that make you who you are. It touches on experiences that everyone has by virtue of growing up. While the protagonists age from 4-and-a-half right through to 17 as the story progresses, I don't consider Razors to be a kids book at all. The subject matter and content, I think, is pretty universal. And the feedback I've had from critics and readers would seem to support that.

It starts as a kind of bedtime story with a malevolent undertone, and as the characters grow it morphs into more of horror/dark-fantasy story with a whimsical sing-song undertone.

The other thing is something that happened when I was eight years old. I had managed to put myself into a two week coma by riding my friend's bike down a steep incline, into a T-intersection, slamming into the gutter and catapulting myself face-first into a tree. I came away with two black eyes that refused to open, a broken nose, a fractured skull that was leaking oxygen to my brain, bedsheets covered in vomited blood and an entry on the Cairns Base Hospital critical list. I told my editor, Dmetri, about it one night, and he decided that was the reason I came up with the character of Walter -- the 4-and-a-half year old kid that grows up in a coma while residing in some otherworldly place with Henry. I had never for a moment put Walter and my accident together, but after thinking about it for a few months I figured Dmetri might have had something there.

TR: The novel combines angelic fantasy, the modern day and also Western-type flashbacks. How did these come together?

CR: It's been said that the best stories don't have just one idea, and that's a tenet I use on just about everything I write. Just about everything I do is a marriage between two ideas I really love, and they're oftentimes ideas that are very different from each other.

In the case of Razors, one idea was Henry: a two-hundred-year-old, ex-alcoholic, Harvard-dropout, no-horse-town surgeon, with a coat full of tools designed to perform a kind of surgery never before seen. But that idea had no context as far as a larger story was concerned.

The second idea came from a conversation I'd had years ago with a friend who was studying in New Orleans at the time. She had told me in passing about her fear of the dark, and a piece of advice her friend gave her about getting over it. Years later I used one thing that was said as an extrapolative launchpad for Walter's story concerning his closet monster. So I gave some thought how Henry and Walter's stories might work together, and a context was born from that.

Suni's chapter was an exploration of the common idea that the little things you lose all go to one mystical home for lost objects. I used his story as an expansion of the universe I'd built thus far with the two stories above, and it grew like that. It's not the usual way a story gets scripted or plotted, it just happened that way, and as a result it was a real education. I took note of things about structure and plot that I probably wouldn't have considered otherwise, by virtue of seeing the whole process from a different angle. It also helped having an undeniably brilliant editor for my first time out.

Razors was a learning experience in the sense that I got to watch the people and places in my head actually tell and develop their own story in a very organic way. One character or set of circumstances influenced the evolution of what came next. I was less of a writer and more of a gardener in many ways, just trimming back unnecessary plot-weeds that threatened to run wild or didn't make the garden look any better, and arranging it all into a more pleasing design.

I felt closer to this story than the others I'd done. Some nights I'd be walking home and fully expect to see Hope walking along next to me.

There was a sizeable amount of material that got left by the wayside; whole plot threads and at least four characters, actually. But I get a kick out of streamlining like that. I'm not all that precious about removing three weeks worth of work if it makes for a better book. Although, there was one character I really wanted to keep just because she had a couple of really funny lines, but in the end I had to let it go. I might bring her back on something else, if she fits with it.

TR: I have also read that roleplaying has been an influence. Tell us about that.

CR: Growing up in Cairns was less than action-packed. I mean, sure, we had fun, we had our bikes, we had the lakes, we had places to take our longbows, we rode a lot, we hung out a lot and we skipped a lot of school. But it was Cairns. My family never travelled at all. Our holidays were always at the same cattle station, every year, when all I wanted to do was at least leave the state. Just once, even. My father and brother were all about fishing and rifles and trucks. I was all about comics and making stuff up. I'm still not entirely sure how I came from a family like mine; by rights I should be a plumber with two kids by now.

I loved movies because that was escapism -- because they were somewhere other than Cairns -- and that's one of the reasons why roleplaying games really drew me in. They were a brilliant meeting point for two things I'd always loved: writing and escapism. So we started there and fifteen years later we were still meeting up, drinking beer, having a few laughs and a really good time.

It was great because I now had a rod for my back as far as writing was concerned: I needed to have new material every week, and it had to be good, because they could be a harsh audience if a game went nowhere. It gave me an early understanding and appreciation of how to engage an audience, how to be true to a character and to treat them in a satisfying way, how to structure a scene or story for maximum impact, how to lay a plot over three or four stories... and we had a great time. It didn't get me polished enough to be publishable but RPG's did keep me going and learning every week.

More than all that, though, they cultivated ideas. Once I started getting better at writing with a view to publishing, I didn't have to sit around wracking my brains for hours trying to find the one thing a story needed. I'd remember something from a game eight years ago and drop it in. The clockwork prison in Razors, for example, is something I came up with for a Vampire game in '95. It was perfect for The Music of Razors, as well as the follow-up short story The Boulevard (which hasn't seen print yet), and if I hadnt had a reason to invent it six years ago, Razors would have suffered for the lack of it.

Most writers keep idea files, and I do too, but I found that RPG's helped stock a mental idea file years before I'd ever thought of keeping one, and that's a real asset.

TR: The novel is marketed by Penguin as Young Adult, perhaps despite its title (and the cover). The novel itself seems to play on children's motifs, then subverts them. Did you have trouble selling the sections where the characters are grown? Was the religious theme a problem?

CR: Firstly, it's actually not marketed as Young Adult, it's marketed as Fantasy. That misconception has caused a few problems for me, actually. The Music of Razors is actually -- by a twist of events that I'll explain in a second -- the first adult novel put out by the Penguin YA department. Unfortunately you're not the only one that's confused it and we've had a lot of bookstores stocking this on the childrens shelves, but I'm told that's all being corrected now. Fingers crossed.

As for selling any of it to Penguin, I had very little trouble, if any, with Penguin and Razors. They initially wanted something for the YA department based on this surgeon character (Henry) that I'd created for the Lothian novella, and I went into it fully intending to give them a YA book, but as the stories developed, Henry's nature and the very nature of the material just shaded itself darker and with more complexity until both I and the people at Penguin realised that it wasn't so much a young adult book any more. And they were cool with it, and Razors became the first adult book the Penguin YA department had under its umbrella. Like I said, it's lead to a few problems with bookstores knowing where to shelve it, but other than that it all went pretty smoothly. I was actually very surprised with just how accomodating Penguin was about the whole thing. I fully expected to be dropped like a hot rock.

As for the religious stuff... well, for starters, Penguin had no problem with it. However, I had a problem with it in that it came across as too Christocentric. What I'd wanted to do was present the whole mythos as something like "There's an element of truth to all religions, there are commonalities amongst all religions, and it is those truths and commonalities that are the Truth". So God is Allah is Buddha is Odin is the Universal Unconscious is blah blah blah. Lucifer may be Lucifer but he's also Loki and every other negative or adversarial component of any given culture's belief system. Unfortunately because of the way the novel is structured and focused I didn't get the chance to properly examine that, so the religious stuff is what it is and uses terms like "angel" and "Lucifer" and all the rest of it. I think Henry's got one throwaway line to Hope about regarding the Godhead, something like "Call it what you like, I just use titles that are convenient" and that was about as far as I could take it without messing up the rhythm of the story.

However, I do know Razors is only half the story. I feel there's one more book left to write, so if I get the chance I'd like to tackle the whole mythos-thing properly in the sequel. Not just the Christocentric thing (which is the least of it), but to resolve the entire Third Option question, the Stricken Angel story, as well as the fates of all the characters. I'd also like to go back and shed a whole lot of light on Henry's origins, his time in Boston with Dorian and the subsequent events that led to Henry fleeing to the west coast.

TR: You have previously written two previous young adult books. Was this a good basis to approach a prestigious publisher like Penguin? Tell us about the two.

CR: I did write a teen-horror novella for Lothian's After Dark series in 1997 (I think), and that definitely helped in getting Penguin to take me seriously. It's the catch-22 of this business that unsolicited manuscripts don't stand much of a chance. You need an agent to submit it for you in order to be taken seriously, but you often won't get an agent until you've been published.

I got lucky with being accepted by Lothian. My girlfriend at the time was friends with a girl who's father was an artist for Gary Crew on the After Dark series. So I got Gary's number, went around to visit him, showed him my stuff (I'd never been published, anywhere, ever, at that point), he liked it and said I should write for After Dark. So I did. It was my first break and made all the difference.

I'd never in a million years imagined I'd wind up writing stuff for a younger market. Still, as long as it doesn't stigmatise me, I don't mind. My main focus always has been and always will be more adult stories, if only because there are less rules about what you can get away with and what is appropriate. It's a much broader canvas and I really enjoy being able to use that.

The upside of doing kids' stuff though is that they're more receptive to the fantastical, and you really can go nuts with those stories, so long as you don't go offending any librarians. After all, they are the ones that actually buy the books.

TR: You have also been a stage director and are writing a screenplay. How do these mediums affect your work? Is there anything else you are going to try?

CR: Movies were my first love I guess, so in a lot of ways writing stories were my way of directing movies. Van Ikin described the effect as "in your face immediacy", and I guess that's where it all comes from. It affects the way I pace a scene and the the sense of rhythm I give it. I also tend to see scenes quite clearly, so I really want to get them down on paper with that much clarity.

I studied theatre for two years and was semi-pro for a little while, and amateur for years before that. I loved acting and miss it like crazy, but the simple fact is that the odds of anyone making it as an actor are little to none. I figure you only live once, so why waste it on a maybe unless you're absolutely driven to pursue that life? I mean, the odds of making a living as a writer are pretty scant, too, but this seemed more hopeful to me, and closer to what I'd really wanted to do.

Initially I never wanted to act, I wanted to direct, and writing was my way of getting there. People like John Cusack got into the whole acting thing laterally, not via Hollywood but via Chicago, a side door rather than the front one. I wanted to try the same thing, the basic premise being to become a successful writer, if I could, and to get one of those books sold as a screenplay. If that worked well, offer to sell the next one for half price in exchange for a directorial credit. Once I get that, I can do a cameo. No idea if it'll work, but it's the plan that gets me out of bed every morning.

Skev, a friend I went to film school with, has been pursuing a career in that industry while I've been pursuing one as a writer, so we're working together getting Razors up as a screenplay. I've got the stories and scripts, he's got the skills and connections and has a good eye for the what works onscreen and what doesn't. The screenplay should be ready to get shown around by the beginning of 2002.

TR: Is the Australian film industry receptive to urban fantasy and the fusion of genres at the moment, do you think? In any medium, is there a type of fantasy that is distinctively Australian?

CR: The film industry isn't one of my strengths anymore, at least not as much as it was six or seven years ago. My impression, from speaking with Skev, is that what distributors are receptive to right now is good scripts. Apparently there's just not enough. So the biggest problem with getting a good script made in this country, as far as I can tell, would be the cost of it.

We've done a tentative budget on what it'd cost to shoot The Music of Razors, and we're still very optimistic. And if that doesn't fly, there's always the next novel.

I'm not sure if there is a distinctive Australian type of fantasy. Maybe I just haven't read enough. Harlan Ellison definitely believed there was a wellspring of talent in this country and he spent a lot of time trying to promote it, but I don't know if there are any particular, distinctive hallmarks of contemporary Australian fantasy.

TR: Tell us about the next novel. What's it about, and when is it likely to appear?

CR: There's two. My baby is a book called Fateless. I wrote the first rough draft before I wrote a word of The Music of Razors, and that was the thing that got Penguin interested in me, initially. I think it's a great idea, but I'd rather keep quiet about it until I get a polished first draft done. I told my editor he could expect Fateless on his desk by February, although now it's looking like it might be a month or two later.

The second thing is an as-yet-untitled steampunk fantasy novel set in a world inspired by the artwork and designs of Dominique Falla. It's a high-adventure tale set in a diverse society of courtly sensibilities, steam-powered high-technology, cultural melange, subverted roles and dead machinery. She's been putting the world together piecemeal for years, and she called me in to renovate it and put it all into some kind of coherent order. If we do our job right, by the end of the book people won't want to leave. We're having a lot of fun with it, trying to make it a complete meal of a story with a lot of different, satisfying tastes in it.

In the past Dominique's worked on things ranging from Children's Book Council award-winning picture books, to tour posters for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and right now she's studying a masters of design and running the official website for the British actor Richard E. Grant. I'm not sure when that particular book will be out, but we're aiming for the end of 2002, if we can.

- Go to Cameron-Rogers.com

©2020 Go to top