Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

Richard Harland

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Eccentric and Extreme

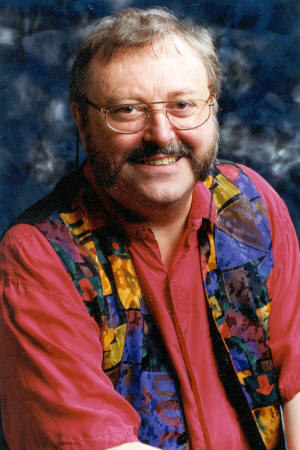

An Interview with Richard Harland

by David Carroll and Kyla Ward, February 2002

What kind of person does it take to chronicle the war against Heaven?

Or create the gothic cult classic The Vicar of Morbing Vyle? Or an expanded

language theory? Must have something to do with being Richard Harland.

With the release of Ferren and the White Doctor, second volume of the

Heaven and Earth trilogy, it is a good time to catch up with this

scholarly gentleman, whom attendees at Worldcon '99 may recall from his

seminar on Postmodern Science Fiction. But don't be scared. Richard has

the gift of making the complex seem straightforward, the astounding

logical and the grotesque really quite familiar. Not that this is

without its dangers. Perhaps, just as a precaution, we should quote the

disclaimer from The Vicar of Morbing Vyle; "The publishers accept no

responsibility for any mental, emotional, or psychosomatic damage

incurred."

What kind of person does it take to chronicle the war against Heaven?

Or create the gothic cult classic The Vicar of Morbing Vyle? Or an expanded

language theory? Must have something to do with being Richard Harland.

With the release of Ferren and the White Doctor, second volume of the

Heaven and Earth trilogy, it is a good time to catch up with this

scholarly gentleman, whom attendees at Worldcon '99 may recall from his

seminar on Postmodern Science Fiction. But don't be scared. Richard has

the gift of making the complex seem straightforward, the astounding

logical and the grotesque really quite familiar. Not that this is

without its dangers. Perhaps, just as a precaution, we should quote the

disclaimer from The Vicar of Morbing Vyle; "The publishers accept no

responsibility for any mental, emotional, or psychosomatic damage

incurred."

Tabula Rasa: I've heard a rumour that you're one of the very few people making a living writing speculative fiction in Australia. Is this true?

Richard Harland: Just about. I suppose I can nearly survive, but I'm not sure I'm surviving too well.

TR: You were born in England I believe.

RH: Yes. I went to university doing an undergraduate degree in England and came to Australia after that. When I came out I had no plan to stay -- I came because Newcastle Uni in Australia offered me a scholarship to do a PhD in something I always wanted to write a PhD on. It was a totally general theory of poetic style -- language and poetry -- and everybody around the world said to me, this is far too ambitious, you can't possibly do it. So I came to Australia, and I didn't do it. I changed to something much smaller and more manageable after a year. But I was only here for a few weeks when I decided that this was the place I wanted to spend the rest of my life. Just the feeling of sun coming down all the time!

TR: What season was it?

RH: After summer. It was still pretty hot, and just a good feeling place. Although I didn't develop my theory of poetic style at that time, about twelve years later, after a lot of bumming around and failing everything else, I finally got to write a thesis that was published.

TR: You started with the theory, then?

RH: My first published book was theory. But I wanted to write novels long before I thought about theory. Ever since the age of eleven or twelve. I'll tell you how it began...

At my cousin's house, which was just down the road, there was an area out the back called the Chicken Run, which was a waste ground with bathtubs and rubber tyres and wooden planks and everything else. Though in my time I never saw a chicken there! We used to build castles and submarines, and develop elaborate adventures that sometimes went on for days and days. When it was raining for a long, long period, as it does in England, we thought we'd write one of these adventures down. We wrote down one, then another and another, and my girl cousin, who was a year older than us, said 'Why don't you try selling them?' We duplicated them -- in those days you had to use a crank handle duplicator -- and took them to school. We didn't actually sell any, because no-one would give us money. They gave us sweets, and comics for swaps, and things like that -- they just didn't want to part with money. That was the first lesson I learned as a writer.

The second was the sheer buzz of somebody saying 'That's great, do you have another?' It's such a thrill, to have reached someone like that. I wanted to be a writer ever after. What I first wanted to write were exciting stories, adventures and such, but I got distracted into literature. Mainly because I won this fairly big prize in England for a short story. It wasn't a good story, only clever -- only because it was written by a kid who'd read more advanced stuff than most kids of his age were reading. It was absolute bullshit, really. But that made me feel I had to go in that direction, writing literary stuff. Which led to me never being able to finish anything.

I had this gigantic, twenty-five years writers block. The only books I could manage to write were theoretical books. They filled the gap, I suppose. It was twenty-five years before I got back to where I'd started, writing the sort of stories I dreamed of in the first place.

TR: This Chicken Run, it seems a little like all your over-grown environments, for example, where the Curs of Space and the Nesters lived. Were you drawing on that in there?

RH: I suppose. But probably not so much the Chicken Run time as a later time, when we made hide-outs in other people's gardens and nearby wasteland -- places over a much wider area. We developed a whole series of hiding spots all linked by secret routes. One was in the middle of a thicket of bush where no-one could ever see us, next to a vast field of allotments. Another was on the top of a shed, out of view, and there were little lean-tos that no-one knew about. There were six or seven special spots that we had, and ways to get from one to the other. It was like a geography that only we knew about.

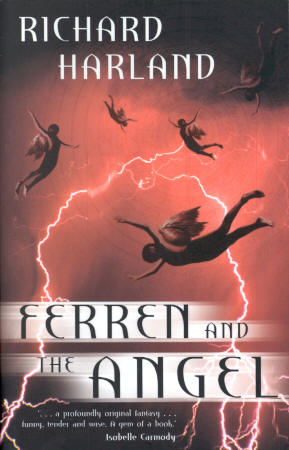

TR: You seem to exert a lot of care in building worlds.

RH: I'd like to think so. And they are often quite small worlds. I hadn't thought about it like that, but it's true, I do write these enclosed worlds, where you have a whole functioning community. With Ferren and the Angel, it was almost a challenge, to make people living on so little actually function as a total unit. The Sea-folk too, with all their luck and taboos.

It does appeal to me, the idea of a fully-created world which is totally real in terms of its own small scale and small conditions.

TR: Let's get back to your thesis material. That was the book Superstructuralism?

RH: Yes. The thesis included Superstructuralism and an early version of my language theory. To get published, I had to cut the language theory out. Then I zoomed in as soon as I could and wrote the expanded language theory, which came out in a second book Beyond Superstructuralism. What I wrote there was the most important theoretical thing I had to say. I guess it wasn't so hard to give up academia in the end, because I'd already done what I had in me to do.

TR: You've had some experience writing poetry and songs as well. Was that the start of breaking away from the literary form?

RH: Not really. I wrote poetry and songs mostly before the theoretical books. The thing about the poetry was that it was short enough for me to finish, unlike everything else. And the songs too.

One song definitely influenced my novels afterwards. It was called 'The Otis Springs Occurrence', and it was the song that always went down best in performance. It climaxes with this incredible pile-up of one event on top of another on top of another. And I've sort of kept doing that ever since... I love huge climaxes where events pile up like that.

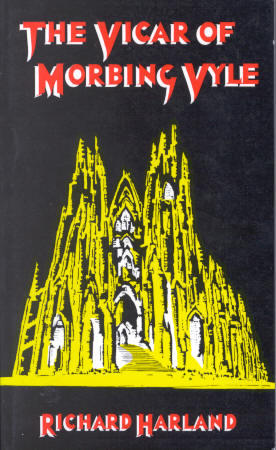

TR: And so we come to The Vicar of Morbing Vyle, from Karl Evans Publishing. Though it says in the front you had another book from the same publisher, called Testimony.

TR: And so we come to The Vicar of Morbing Vyle, from Karl Evans Publishing. Though it says in the front you had another book from the same publisher, called Testimony.

RH: Yeah. It's sort of complicated, because Karl Evans Publishing went through two totally different phases. The first phase was a guy in Balmain, who was into publishing without knowing a lot about it, and who was interested in literary stuff. He brought out Testimony, which was basically a collection of all the poems and short stories I'd had published in literary journals. And then he dropped out of publishing, so he was happy to pass the name on.

TR: Was there an actual Karl Evans?

RH: No, I don't know where the name came from. I wish I did.

TR: So what was the inspiration for Morbing Vyle?

RH: I think it was the characters. I had these ideas for very weird and bizarre characters -- and of any book I've written, The Vicar was the one where the characters are most separable from the story. It's probably the only time the characters came long before the story.

TR: Was this when you overcame your writers block?

RH: Yeah. But not all in one go. I wrote the first forty or fifty pages without a break -- I remember this incredibly high, to be able to write that amount in a day-by-day way without getting stuck. It was wonderful. Then I got stuck! But I'd had the experience, I knew it was possible.

I came back to it a year or so later, and got half-way through, and then in another year or so I got two-thirds through. Eventually I finished it all. Then I had to go back and revise it. So it didn't come out easily.

I say 'writers block', but it was also writer's inadequacy. I wanted to do things that I wasn't yet capable of doing. It wasn't only me not feeling sufficiently inspired.

It's like, well, not having the talent to realise the visual images in my head through painting. I have this weird visual thing, I'm not sure what mood it depends on, but sometimes I start seeing a very rapid turnover of images, quite surreal images -- with beautiful colours, incredible colour combinations -- and they just flicker by. I start thinking of the image and it becomes something else, then something else again, and on and on. I'd love to be able to turn that into pictures, but I know I don't have the skill of actually putting stuff on canvas or paper or whatever.

As a writer, I don't think my imagination has improved -- whatever it is now is what it always has been. My ability to write out and communicate my imaginings is what's changed. The Vicar of Morbing Vyle involved quite a number of attempts, but I started further ahead than I ever had before, and each time I got a little bit closer. By the time I'd finally written that novel, I was at the point where I could keep on doing it.

TR: There's a rumour of a sequel...

RH: The Black Crusade. Yeah, it's finished but I don't know when it will appear.

TR: A little less mainstream than Ferren?

RH: I don't think in terms of mainstream or non-mainstream, they're just different things I like to do. The Black Crusade, for various reasons, I can't see appearing from a mainstream publisher. Some of the things I do are commercially publishable, some of them aren't, but to me they're all my children!

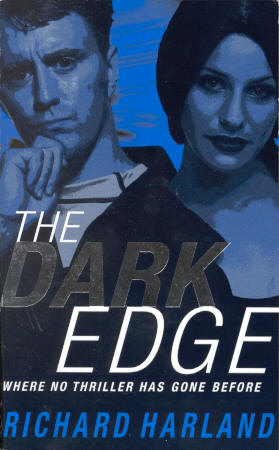

TR: After Morbing Vyle came the Eddon and Vail books. How would you describe them?

TR: After Morbing Vyle came the Eddon and Vail books. How would you describe them?

RH: I would describe them as science fantasy. I've always like SF, it goes back to when I first started reading, so that came very naturally. But the novels aren't powered by scientific or technological ideas. The first Eddon and Vail book, The Dark Edge, was originally called The Darkening of Planet P-19, and my first, dominant vision of that novel was a world under a curse, where things were warping out of normal, everything was sickening and going wrong. When I came to the idea of putting a detection narrative into it, where there would be people investigating and working towards the true cause through various possibilities, that seemed to go well with a science-fiction-ish world. But it's better to call The Dark Edge science fantasy. It probably wouldn't have been too difficult to turn it into an outright fantasy. It wasn't that I suddenly decided I wanted to write SF, it was that the possibility of a SF-type world opened up a space for the imagining I wanted to do.

TR: The books seemed to have been marketed in quite a different way.

RH: Yeah. If you look at the publishing scene at the time there had been a bit of a burst of publishing science fiction, and Pan Macmillan had been at the forefront of it. Australian science fiction had done okay in Australian sales, but it was starting to lose audience. You can see it more clearly now -- we've got to the stage where the amount of Australian SF sold here is only a fraction compared to Australian fantasy. The publisher's idea was that if it could expand the audience by drawing in the audience for thrillers and detection -- and the interest is there in the novel's narrative -- we could overcome this shrinking audience. I think there were problems with that. I think someone who reads science fiction can be interested in science fiction detection, but somebody who is really into detective stories isn't going to want an SF-type context. They just won't get into it. The Eddon and Vail novels were trying to encourage non-SF readers into sampling SF -- but in the end, the novels were read mainly by existing SF readers.

TR: It was a bit hard to tell what sort of novel it was, from the cover at least.

RH: Yeah, well. I think it was a justifiable idea, but the way the SF market has gone since, it was pushing up-hill. I'm glad to have moved across into fantasy, since fantasy was probably my deepest inclination anyway. And it's no longer a struggle against market statistics that have nothing to do with the quality of the book. I think science fiction readership has declined in Australia because so many male readers have stopped reading.

TR: Book four exists, doesn't it?

RH: No. It half exists. Just slightly less than the first half was written, and things weren't right with it. I could see how it needed changing, but it would mean going back to the beginning and rethinking. I started writing it without a contract, and when I didn't see a contract coming through from Pan Macmillan -- partly due to the fact that I was moving to Penguin, which didn't help -- I didn't have the heart to go on with the rethink. I still believe there were some really good things in that fourth volume which I can use in other ways. Nothing gets lost in the end. What was good will always find another home.

When you write your first novel -- I think this is true of The Dark Edge, but maybe not Morbing Vyle -- you want to put everything in. But the more you write, the more you realise that things have their natural home -- and you don't have to cram it all into the one novel.

TR: Why angels?

TR: Why angels?

RH: Ulp.

I wonder if I've always had this thing about angels. My two favourite books of poetry -- and this goes way back, years before Morbing Vyle -- are the Duino Elegies by Rainer Maria Rilke and Concerning the Angels, by Rafael Alberti. Rilke is my all time favourite lyric poet and a sort of mystic, although not in a Christian sense. When he invokes angels in the Duino Elegies, he casts them as terrible and unknowable -- as something in the human psyche if you like, an eternal symbol. Angels represent the terror of beauty and the beauty of terror -- no, actually, I'm bullshitting there. I'll stick to the terror of beauty, that's what I meant!

Alberti in Concerning the Angels creates all these different named angels, and again they're not exactly religious angels, but represent something out there, something beyond ordinary life. I think it's the idea of something beyond ordinary life that has always appealed to me.

I had a completely unreligious upbringing -- my family weren't even committed atheists. I was sent along to church, because it didn't matter either way. If I'm very drawn to religious imagery, it must be because I was deprived of it when I was young!

TR: There have been more and more books on angels of various types. Is this your niche you've found?

RH: Whoa! I don't want to be in any niche for too long. There was a period of angels a little while back, which was very post-New Age, where everybody had their own little personal guardian angel that lovingly watched over them. That's not my idea of angels at all. In a sense, without being religious, I'm more religious than that. Angels are awesome beings, they don't exist to 'make-the-world-nice-for-you'. In my Heaven and Earth trilogy, the angels are warrior angels. You wouldn't want to pat them or stroke their wings -- or if you did, you'd be sorry.

TR: What about Miriael? Was she a way to humanise these fierce angels?

RH: Sort of. I guess there are two aspects to that. Miriael is a warrior angel, and even though she's fallen to earth, she looks down on anything that is less than angelic, anything physical, earthly, low... She sees Ferren and he's dirty, disgusting and smells, and she dismisses him for not being pure and strong as she is. That's a human-like elitism that might go with being an angel, I think. But then she changes over the course of Ferren and the Angel and comes to relate to human beings. In Ferren and the White Doctor she still hankers after Heaven -- as you would. If you've come from Heaven you would never...

TR: get over it?

RH: Exactly.

Do you want to know how Ferren and the Angel began? It came from a dream. I was crawling underneath a tarpaulin, and lifted it up, looking out from under the edge. There was this vast night sky, with strange glows and lights moving around it, and boomings and words. I knew -- the way you know things in dreams -- that this was a war between the forces of Heaven and the forces of Earth. I woke up and thought, wow, I wonder if there's something in this. What if one of those lights got shot down and crashed to earth, and that light was an angel? Totally undeserved! The germ of the whole thing just given to me... as set down in the first five pages.

The way I'd dreamt it also set me on the best possible track for a human focus. Because the person observing -- me in the dream -- was someone different to the forces of Earth, even a bit scared of them. So when I ultimately came to develop a historical myth, I produced an explanation about how human beings had explored the boundaries between life and death, and with advanced medical technology had managed to bring a human being back to life, who had reported on the existence of Heaven and of angels, leading to scientific exploration, leading to warfare between Heaven and Earth... To come to the state of the world in the original dream, there had to be a divergence within the forces of Earth -- those who were fighting against Heaven, and those who were merely outsiders. That I feel was very lucky for me, because it gave me a position neither simply pro-Heaven nor pro-Earth.

You can't have a centre of sympathy that is with Heaven -- I mean, it wouldn't be a very human position, it would be an abstract position. But I also wouldn't have wanted to be totally on the side of the Earth against Heaven, because I find the idea of Heaven -- regardless of truth or belief or anything -- quite awe-inspiring and emotionally moving. So it was the artificial non-human beings fighting against Heaven who became the bad guys. So bad, there's nothing positive you could say about them -- well, maybe a psychologist could say they weren't hugged enough when they were young. [Laughs]

Ferren is one of the original human beings, the ones you sympathise with, and they're moving closer to an alliance with Heaven. But their success is a human success. I guess I see the point of view of the novel as humanistic with reverence. Does that make sense? In a way the trilogy is about humans rediscovering themselves, and rediscovering their powers after having been degraded and cowed and stomped on for so long. The excitement of actually building a civilisation again -- hopefully a better civilisation -- but combining that with a reverence for the terrible beauty of angels.

It's a bit of a complicated position, I guess.

TR: What about Doctor Saniette. Where did he come from?

RH: I know where the name came from, at least. It's from A La Recherche du Temps Perdu, by Marcel Proust. There was a character in about the second volume called Saniette, a minor character. The name just stayed with me. What I like about it is that it's a very sinister name -- very sweet-sounding, but something sinister underneath.

TR: What about your other names? Do you spend a lot of time on them?

RH: Yeah. The people in Ferren and the Angel have earthy dull names, so they're mainly mono-syllables. I keep playing around with sounds, and saying things out loud until I hit something that sounds right. The Sea-folk have a different quality of names, harsh-cry type names, which goes with the sea environment somehow. One thing I hate about some fantasy is the sheer uninventiveness of the names, where the author has just pieced a whole heap of syllables together. Tolkein never did that -- he knew how a name grows. His names are totally persuasive, because they really are the way that language forms names. And often it's the names that are a little bit odd-sounding that are the true ones. If you think of the names of people you know, some of them are sort of implausible -- and yet there's a rightness about them too.

TR: Was there any influence the setting of Eastern Australia had on this? Or didn't it matter?

RH: Not really, I don't think it matters. I thought I'd simplify things a little bit by setting Europe and Asia on fire forever, which focuses attention on more important places. [Laughs] But it probably could have been somewhere other than Eastern Australia, and I wouldn't have made any changes.

TR: Where you thinking of any particular terrain in NSW?

TR: Where you thinking of any particular terrain in NSW?

RH: No, it was more like the other way around. Having got the terrain, I had to find bits of NSW that would fit it.

TR: So number two has just come out. How is number three going?

The third book, Ferren and the Invasion of Heaven, is already written in first draft. It's very satisfying to look back and see how it all fits together. Ferren and the Angel was written as a single separate novel, and it wasn't until I came to think of showing it to a publisher that I realised that maybe I ought to be suggesting there could be sequels. And I realised, yeah, there could be sequels... At the end of volume one, Ferren is going off with Miriael, looking to form alliances with other tribes, and I started thinking about what might happen next. To me it was as if there were the necessary seeds in the original novel which wanted to grow in certain directions. The second novel expands the parameters of the world, and the third novel brings it all together in a very satisfying way. I have a feeling you could read all three novels, and think they were planned as a whole from the beginning.

Even the Morphs... the Forest of the Morphs was just one place that Ferren went past on his journey towards the Humen camp -- I needed some interesting things to happen along the way. But having invented the Morphs in their forest, I had to explain them -- and the explanation is that they're souls of humans unable to ascend to Heaven. Then it became obvious that they could have a much larger role -- they're one of the four major types of being, along with Humen, Celestials and Residuals. I didn't develop it any further in the first version before the novel went to the publisher, but I knew I'd done something good in the Morphs chapter. Then my editor at Penguin -- well, Dmitri is one of those great editors you dream of, because he is so fully in sympathy with the novel. I don't take to suggested revisions very readily, but Dmitri can make creative suggestions that expand on my initial creative ideas. And he realised that the Morphs have big possibilities, he saw how they could be brought in later, namely with the death of Neath. The more I thought about it -- and then thought of how an angel might see the Morphs -- the more I got excited by it. The role of the Morphs has kept on growing ever since.

Ferren and the Invasion of Heaven won't be out until at least February next year. I still have the structural revisions to do.

TR: You do seem to have a knack for absolutely unique characters.

RH: I do like characters in whom the flame of individuality burns very strongly -- often eccentric characters, or extreme characters in one way or another. Still realistic -- to me there's a difference between caricature which is something someone else imposes on a personality, and characters who have their own vitality and energy that springs from within -- even if they only play tiny roles. Marassa Dolor had a small role, but I could write novels and novels with Marassa in them. Except that she died. But she could come back! She's the sort of person who could come back... these characters have enough life in them to keep living and living.

I think that in Ferren and the White Doctor, the characters are a little bit more developed -- I spend more time on them. When The Dark Edge came out, I didn't expand on characterisation a hell of a lot, and my editor at Pan Macmillan said, you do characters well, so keep at it. I thought, well, I enjoy it, it's what I want to do, I just thought I had to be more strongly action-focused. I still am action-focussed, but I love developing characters -- characters who burn very hard and hot. I'm not into slow moving, realistic characters that take a hundred pages to warm up -- I want intense characters, but I want them to be psychologically real, to be very, very interesting as individuals.

TR: What is the strangest thing you've ever written?

RH: The Vicar of Morbing Vyle and The Black Crusade are extremely bizarre -- The Black Crusade even more so than The Vicar. But maybe the strangest of all was a prose poem that came out in Testimony, called 'Land'. It was from when I was living at Coalcliff, south of the Royal National Park, in a very black period of my life. I'd go down to the rocks by the sea -- there was actually a swimming pool there with rocks all around. The waves would come in, and froth and surge through the channels between the rocks. One night, I started telling a story about myself as a tiny little figure hanging to the rock in one of those channels. It was fiction, but it was also me, really being there in Coalcliff -- shipwrecked in the story, feeling shipwrecked in real life. Then the story continued over several days as I 'explored' along the beach -- places where I used to walk. I'd named the places in my own head even before they entered into the story -- the Leopard Rocks, the Standing Stones, the Inland Sea. All the places were a small geography that became a much larger geography. Things that were happening in me at the time were transferred onto being shipwrecked on this particular beach.

There's actually a map which goes with the prose poem, of that area with the swimming pool taken out. [Laughs]

TR: Most of your books have maps.

RH: I love maps. Aileen will tell you that. I've got atlases I can dwell on for hours on end.

I think a lot of people who are into fantasy love maps, and love thinking of worlds in a map-like way. One thing that often comes up in my novels I've realised is the panoramic view -- where someone is standing up high and looking out over a wide expanse.

TR: What is the strangest reaction you've ever had to your work?

RH:I don't know. Sometimes people find unexpected things in the novels that I'm pleased about, because I'd like to believe they're there. Sometimes, and this goes particularly for some people I know at university, they manage to find things that I hope to hell aren't in there -- because if they were, I'd be embarrassed at my own stupidity.

One thing that is curious about people's reactions is how often they want to relate things too directly to life. If you create a character, who does it come from in real life? It's as if there was some kind of direct feedback all the time. Really, there isn't. Everything relates to life, but the distance is so great in fantasy that no-one has a chance of tracing it except the author. And most of the time I can't either. There's an imagination that goes way, way beyond the things that directly happen to you.

TR: What is coming up after Ferren?

RH:Three or four days ago, I started writing a new Young Adult fantasy, which is totally different to Ferren -- more gothicky, even a bit Mervyn Peake-y. It's something I've had ready to write for a long, long time. The first idea of this novel goes back almost as far as the first idea of Ferren, which formed something like nine years before Ferren and the Angel came out. This new one -- called Juggernaut -- has been building up for a similar amount of time. I've finally got it developed to the point where it has to be written -- I can't hold back any longer!

Speaking of names as we were, you'd like some of the names in Juggernaut. For example, Sir Mormus Porpentine and his wife Ebnolia. Along with Bartrim Gibber and Septimus Trant.

TR: We saw you give a talk on post-modernism in Melbourne once. Is your writing post-modern?

RH: No!

[Laughs]

I used to lecture on post-modernism, so I know what I dislike. There's a real post-modern sensibility which affects all of us -- it affects all kinds of cultural forms. I feel I'm a part of that. The Vicar of Morbing Vyle and The Black Crusade couldn't have been written in any other period -- that bizarre edginess, the tastelessness, the grotesquerie. The Black Crusade has aspects you could call post-modern in the sense that Monty Python is post-modern. One of the things about it is that the publisher keeps complaining about the author for failing to maintain suspense and the author keeps insisting that his story isn't a fiction.

But I hate literary post-modernism. I feel it's up its own fundamental orifice. It's bloodless and it's made writers extremely precious and self-conscious. As far as I'm concerned, I want to tell good stories, imaginative stories, in a way that appeals to people just as much now as it ever did. I guess one of the things about Young-Adult writing is that you touch base with a totally genuine response. If your readers aren't enjoying the novel, they'll put the book down and that's the end of it. As simple as that. Either you get them in or you don't. There's no bullshitting around with -- 'Well, it must be good because it's terribly clever, isn't it? So profound and metaphysical?' So profoundly bullshit. I think literary post-modernism is a dead end.

This is me as an ex-lecturer in English Literature -- but I think there's a parallel in the past. In the period before Romanticism, poetry had got very self-conscious and precious, with poets after Alexander Pope. The poetic diction, the conventions, all the games you had to play. It became a cleverness that was really very detached from experience and feeling. The Romantics overthrew that, and went back to something they could genuinely respond to. They also picked up on a genre which until then had been viewed as inferior, only for 'less-educated' people -- the Gothic genre. They found that it had the energy that was lacking in the poetry they were reacting against. I think exactly the same thing will happen in our time. Literary people have been fond of viewing fantasy as inferior, as appealing to 'less-educated' people -- but fantasy has the energy and vitality and the creativity that current literature lacks. The future of storytelling grows from fantasy. That's where it is, that's where it's alive.

Bibliography

- Testimony, Karl Evan Books, 1981

- Superstructuralism: The Philosophy of Structuralism and Post-Structuralism, Routledge Kegan & Paul, 1987

- Beyond Superstructuralism: The Syntagmatic Side of Language, Routledge, 1993

- The Vicar of Morbing Vyle, Karl Evan Books, 1993

- The Dark Edge, Pan Macmillan, 1997

- Taken by Force, Pan Macmillan, 1998

- Hidden from View, Pan Macmillan, 1999

- Literary Theory from Plato to Barthes: An Introductory History, Palgrave, 1999

- Ferren and the Angel, Pengun, 2000

- Ferren and the White Doctor, Penguin, 2002

- Ferren and the Invasion of Heaven, Penguin, 2003

Websites

- Richard's homepage

- Penguin Australia publishers of Ferren

©2020 Go to top