Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

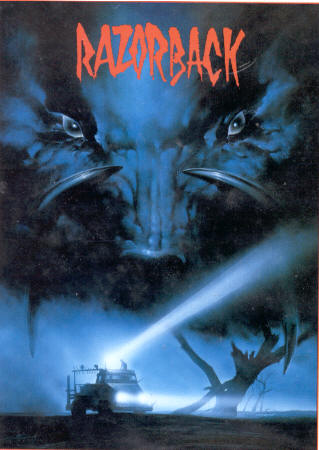

Razorback

OTHER HORROR PAGES

Razorback

Directed by Russell Mulcahy, 1983

A Review by David Carroll

"I don't know. There's something about blasting the shit out of a razorback that brightens up my whole day."

"I don't know. There's something about blasting the shit out of a razorback that brightens up my whole day."

Depending upon how you define things, Razorback is perhaps the most recognisable 'horror' film from Australia. It has a rising young director in the form of Russell Mulcahy, some reasonably well-known faces, both Australian and American, and a giant pig. It also has a depiction of the Australian outback as, basically, hell.

The film starts off following the exploits of Beth Winters, animal activist and journalist. Apparently kangaroos are being exploited for dog food and she's been sent out to do an exposé. It's actually not that unreasonable a premise (last month there was a court case over whether the ABC was allowed to show illegally obtained footage of cruelty in possum processing plants -- they were), although I'm less sure people would come all the way from the US for such a story. With her local cameraman in tow (played by a youngish looking John Howard -- insert standard declamation against our PM here) she soon runs into far more trouble than she was expecting. Giant pigs may be the least of it -- the human population ranges from hostile to out and out psychotic.

It's not unusual for giant monster movies to include human stupidity and malice as a fundamental part of the equation, exasperating a bad situation ("of course tourists being eaten by sharks will help the community", not to mention "trust the company, Ripley, it's your friend"). Razorback handles it a bit differently. In a way, the brothers who work out at PetPak are the real villains, and the pig is merely a big dumb animal, best avoided. But even that isn't quite right. The brothers, their factory, the nightmare landscape and the pig itself, are all presented as a single, coherent malevolence. I have written previously, in more than one place, that the landscape is the defining feature of Australian horror. Razorback extends the idea into expressionism. It's not just the dream sequence (wherein we get just about every extreme of inland Australia -- except for the waterhole, anyway -- in about 30 seconds), nor the somewhat clunky lightshow in the final battle which gives the whole thing its air of unreality. (Not even the shot of half a house -- and Don Lane -- trundling off into the desert.)

When Beth Winters first gets to town, everybody turns against her, but when her husband eventually arrives, the reception is a lot friendlier. This is not just the normal sexual archetypes of horror films either (although that plays a part). The old hunter Jake Cullen is also given the pariah treatment after the death of his grandchild. The message is that as long as you go with the flow, life is fine, if not exactly idyllic. Once something goes wrong, or you kick up a fuss, you're fair game from every direction. This is especially clear in the character of Sarah Cameron, a mostly pragmatic and sympathetic member of the supporting cast, who lives on her lonesome close to PetPak and its psycho rapists with no trouble at all.

Of course, all this unnaturalistic splendour could just be attributed to shoddy film-making, but I don't think so. The change in tone and the way things are shot in different locations, such as Sarah's farm and the factory, is very striking, whilst the town itself shifts between the two. There seem to be two different realities, and a slippery border between them. I'd be interested how Peter Brennan's source novel approaches the matter, but I haven't found a copy (Kenneth Cook, whose novel Wake in Fright seems to have inspired a lot of these starkly negative portrayals of the outback, also wrote a novella called Pig in 1980, strangely enough).

Expressionistic or not, it's all pretty well made. The actors never seem really comfortable in the first half, though that improves quite a bit. David Argue as Dicko, one of the brothers, is especially memorable, and Bill Kerr (Jake Cullen) does well. Gregory Harrison grows into his hero's role, as is appropriate, and Judy Morris makes the best of a somewhat thankless job as Beth (the sort of character that can come across as very contrived -- a supposedly hard-hitting journalist who is immediately out of her depth. This is avoided, as the character's vulnerabilities are shown early, and she is definitely making a strong go at her assignment, in her own awkward manner). On the other side of the camera, Russell Mulcahy makes his presence felt. He had a background in directing video clips (as it proudly proclaims out my video sleeve) and then went on to make Highlander not long after -- an interesting double. He's done a surprising variety of other things since then -- from one of the better millennium movies, Resurrection, to episodes of Queer as Folk and, I'm afraid, Highlander 2. The pig itself (I should of course be calling it a boar -- although descended from European stock gone feral, the razorback is a distinct and dangerous breed) is handled very well. You can never get a really good look at it, but its size, power and energy are clear. Although a little peripheral to the centre of the movie, it is a strong presence at the beginning and end, and never forgotten.

In the end, I think it is the movie's pitiless and fascinating presentation of Evil -- in animal form, in the land, and the social constructs of the population -- that gives it its impact. I don't think time has treated it well in the memories of most people, but it is not out of place as the pinnacle of the big, mean and furry end of Aussie horror films, and is deserving of more than that as well.

- External link: IMDB listing.

©2020 Go to top