Australian Horror

INTERVIEWS

Robert Hood

ARTICLES

Finding Carnacki the Ghost Finder

OUR BOOKS

INFORMATION

REVIEWS

809 Jacob Street, by Marty Young

After The Bloodwood Staff, by Laura E. Goodin

The Art of Effective Dreaming, by Gillian Polack

Bad Blood, by Gary Kemble

Black City, by Christian Read

The Black Crusade, by Richard Harland

Black Days and Bloody Nights, by Greg Chapman

The Body Horror Book, by C. J. Fitzpatrick

Clowns at Midnight, by Terry Dowling

Dead City, by Christian D. Read

Dead Europe, by Christos Tsiolkas

Devouring Dark, by Alan Baxter

The Dreaming, by Queenie Chan

Fragments of a Broken Land: Valarl Undead, by Robert Hood

Full Moon Rising, by Keri Arthur

Gothic Hospital, by Gary Crew

The Grief Hole, by Kaaron Warren

Grimoire, by Kim Wilkins

Hollow House, by Greg Chapman

My Sister Rosa, by Justine Larbalestier

Path of Night, by Dirk Flinthart

The Last Days, by Andrew Masterson

Lotus Blue, by Cat Sparks

Love Cries, by Peter Blazey, etc (ed)

Netherkind, by Greg Chapman

Nil-Pray, by Christian Read

The Opposite of Life, by Narrelle M. Harris

The Road, by Catherine Jinks

Perfections, by Kirstyn McDermott

Sabriel, by Garth Nix

Salvage, by Jason Nahrung

The Scarlet Rider, by Lucy Sussex

Skin Deep, by Gary Kemble

Snake City, by Christian D. Read

The Tax Inspector, by Peter Carey

Tide of Stone, by Kaaron Warren

The Time of the Ghosts, by Gillian Polack

Vampire Cities, by D'Ettut

While I Live, by John Marsden

The Year of the Fruitcake, by Gillian Polack

2007 A Night of Horror Film Festival

OTHER HORROR PAGES

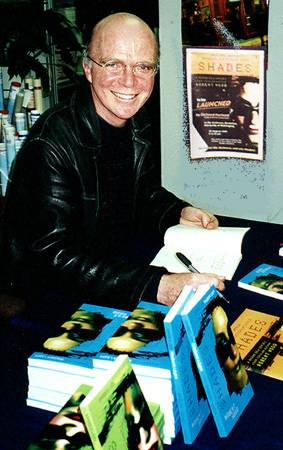

Under the Hood

An Interview with Robert Hood

By Kyla Ward, 2001

Robert Hood is a writer. One of those people you feel simply couldn't not write. His short story output is enormous, and includes the 1990 Australian Golden Dagger award for crime and entries in The Year's Best Horror Stories #19, Dark Voices #3 and Dreaming Down-Under. Crime and horror, science fiction, fantasy and magic realism, his range is equally wide (although he does like zombies).

But it's when you discover his work for children and young adults that things get really scary. With Bill Condon he co-authored the children's series Creepers. In 1999 his first novel Backstreets was published. And now there are the Shades.

I recently talked to Rob about this exciting new series, as well as projects current and future, publishing, and why Australia is the perfect place to encounter the strange.

Tabula Rasa: Well, just to start off with, how about you tell us something about 'Shades', the author's perspective. I believe the fourth volume has just been released.

Robert Hood: Yes, Black Sun Rising, nice and apocalyptic, has just hit the shelves -- not apocalyptically yet but hopefully it will be.

What to say about 'Shades': well, the original idea for 'Shades' came from simply the desire to develop a series based around a supernatural concept or creature that wasn't too obvious, that hadn't been done a million times. Vampires have been done a lot, other ones have been done a lot. I'd been playing with ideas related to ghosts and the dead that aren't quite dead, and I thought I'd play with that concept a bit more. Gradually the idea that maybe they're not dead at all but something else is going on -- originally, actually, what's known in the books as the Shadow Realm or Tenebrae was called the Death Realm, so it was specifically death-related. But the publishers in the very early stages -- we're talking about the original outline -- wanted me to make it less obviously horror.

TR: It was always a young adult series?

RH: Yes.

TR: They wanted something that was supernaturally themed?

RH: Not necessarily supernatural at all, it could have been science-fiction. In fact, what I did was take what was a very supernatural expression, that is 'Death Realm', 'Ghosts', etcetera. And started to couch exactly the same outline I'd done to make it sound science-fictiony by talking about alternate dimensions and dark matter and all that sort of stuff. So gradually, that evoked the idea of shadows and everything that relates to that, and I started to develop the mythology that lay behind it. A lot of the details weren't formed then of course -- they were developed as I got down to the nitty-gritty of elaborating the plots of the individual novels, specifically as related to the characters because at about that point the characters took over in interest. I developed Nathan and then in particular Cassandra, who was just an accident while writing the first book. She took on certain characteristics that I really liked, and when I wrote the second book I could go to town on exploring her. All of the four, main narrating characters were developed before the first novel was written.

TR: What you have said suggests that the development process was very structured.

RH: It was; it had to be. The publisher wanted outlines. I'm normally not that structured when I write. I develop structure as I go along and then go back and insert the structure that wasn't necessarily there to start with. I find that fixing everything in stone too far ahead takes away some of the creative energy for me. I like the serendipity that occurs when you're writing as things get connected that you wouldn't have thought of connecting, and that evokes a whole vista of other possibilities which get incorporated. And despite whatever structures I had developed at the beginning of 'Shades', if you read the original outlines you'll realise it went all over the place other than there. It changed as it went along. Which didn't really create any problems, it didn't worry the publishers except that in some instances they had already designed some pre-publicity based on those early outlines, which had to get changed.

TR: In the 'Shades' books you unveil a very wide-ranging vista, as you said, but it's also in many ways an Australian vista.

RH: Well, whether it's because I live here and that's what I familiar with, I do think of things as being Australian while I'm writing, even if I'm not using particular places or particular cities -- like in Backstreets where what's obviously Sydney is referred to as 'The City' and never actually referred to as Sydney. The publisher didn't want it that specific, but also I didn't want to do it that specifically because I found I wanted to violate the actual geography of Sydney while I was writing. Rather than worry about that as an issue for people to pick on, I made it some sort of generic city rather than Sydney, so for example I could make the distance between Wynyard and the outer western suburbs a lot shorter than it really is.

TR: The geography of 'Shades' feels like Wollongong.

RH: That's right; it is different, I was thinking about different things, an imaginary community, but it is certainly based on Wollongong, the cliff-side mining communities and the like. Of course, the last book is set in Egypt, so that's rather a change. Hopefully the Cairo setting doesn't come over as too Australian.

TR: You say you tend to work naturally in this Australian environment. Would you say that it holds any particular problems for -- well, if 'Shades' aren't really horror--

RH: Oh, you see the 'not really horror' thing; that was selling the idea to marketing. The publisher herself was quite keen but it had to go through marketing and they were saying at the time 'no horror'. Therefore I couched the outline that it sold on initially in these fantasy/science fiction terms, but when I wrote it I was just writing horror. And it's okay, because they've accepted it and liked it since then. Their idea of what horror is wasn't fulfilled by what I was presenting to them, so they dropped that whole idea. It's one of those marketing prejudice things; every now and then they get it into their heads that horror doesn't sell, which is why so little of it gets published in Australia.

TR: So you think it's the marketeers rather than any difficulty with an Australian setting, all that sunlight and sand?

RH: Sunlight and sand is a perfect environment for horror! I mean, the old dark castles on the hill aren't necessary for horror, and evoking horror in the bright sunlight is a very effective way of doing horror.

But I started out just getting away with writing horror novels by not calling them horror novels and once it got started, they were quite willing to go along with the idea that they were horror then, and that's what the publicity says; these are horror novels, I'm a horror writer.

TR: Do you like that? 'Robert Hood, horror author'

RH: Yeah, that's fine. I've always said that. It does at times seem to restrict what you're capable of doing in people's minds and I write a lot of other things as well, but there is a darkness... Backstreets is theoretically not a genre novel at all, but it's very dark.

TR: But there's also 'Robert Hood, young adult author' and before that 'children's author' with the 'Creepers' series. You have written for a number of different age levels. Do you methods of writing or of approaching the subject differ in these cases?

RH: Only for writing for very young kids, which I still do. I really enjoy genre stories, including horror, for that age group. I'm doing things like 'Creepers', I gather successfully, because they keep asking me for more -- for Pearson's Educational with 'Spin Outs', the series edited by Paul Collins and Meredith Costain. 'Spin Outs' is very short stories and the other series that was originally 'Trends' but which is now called 'Awesome!' is longer stories that are published as separate novels. They're not really novels, they're 4,000 to 8,000 words.

TR: Trainer-novels.

RH: But they're fun. Because there is one thing you can do with kids that you can't do with adults so easily, and that is be utterly extravagant with your imagination. You can really go to town with weird stuff.

TR: You reckon adults don't accept that?

RH: You have to stick within certain parameters when you're writing for adults, otherwise they won't accept it in the first place. If you're lucky, you can go beyond those parameters once you get going.

TR: Once you've established the rules.

RH: But I've found that writing this kid's stuff, particularly in a short form, you don't have to rationalise it for them. It just is, and they'll accept that.

TR: Give me an example of extravagant imagination.

RH: Well, the 'Creeper' stories were a good example. In Humungoid, the monster of the mountain actually was the mountain, which was why no one could see him because they kept seeing the mountain. You can do all sorts of stuff and the rationality of it isn't particularly of interest to them as long as it has its own artistic consistency. You can do this for adults, but you have to do it in a slightly different way. Another example is 'The Monster Sale', where an intergalactic merchant turns up at a local fair, selling real monsters. Or 'Pests', in which a girl is tormented by these little creatures which are continually getting her into trouble -- "I didn't do it!" she says all the time. Very familiar!

It's been fun writing those sorts of things for kids, but there is a down side. Some of the kids stories that I've been writing are also for the American market; the American education market. It is extremely proscriptive and demands that certain things don't happen and that other things do happen. That can be a bit tiresome.

TR: What kind of things do you mean?

RH: It comes from the fact that they are hypersensitively concerned by how events in stories will be preceived and, I guess, by the concerns of parental groupings. Ethnic mix, not showing minority group members doing the wrong thing, violence, etc, etc. No pointed sticks.

There are all sorts of restrictions. Writing fantasy stories without any trace of magic is one of my favourites.

TR: Still! Post-Potter and all--

RH: Oh especially, I suspect. It's fine in Australia but the American side of it is still, 'no, don't want that. It might lead to Satanic activity'.

TR: Do you know if any readers of the 'Creepers' series have grown up into 'Shades'?

RH: No, I don't. I have met a couple of kids at book events that have read both 'Creepers' and 'Shades' which interested me, because when I was writing 'Shades' I wasn't thinking kids literature at all. I was thinking teenagers, sixteen years old or around that age group, which is to say adult readers really with some variations, whereas with 'Creepers' I was definitely thinking kids. And some of these kids I met who'd read 'Creepers' and were now reading 'Shades' aren't that old. The publisher kept advertising 'Shades' as twelve and up, which seemed very young to me, but in fact twelve is getting onto early high school and these kids are starting to read adult books. So they're quite capable of reading 'Creepers' on one hand and enjoying it, and then reading 'Shades' which is a whole new kettle of fish.

TR: How do you reckon TINOTS would go up against the Shades?

RH: Um, well -- that's a very hard question to answer because they work in different universes.

TR: That's true. But we've been talking exclusively about 'Creepers' and 'Shades', where you've actually done a great deal of other work. I'm going to ask you what you think is one of the most mature, adult if you will, pieces of work you've ever done?

RH: Oddly enough, though I suppose it will be obvious when I say it, I think Backstreets is. It's one of the most serious pieces I've written and one of the pieces I was most emotionally involved in, for obvious reasons, having concerns about death and the death of my own son. But I think that's one of the best things that I've written. It's certainly one of the most personal, although everything relates back to me one way of another in the end, no matter how removed it seems to be. And people have the idea, of course, that if it has fantastical elements in it then it's not personal. But that's because there's an awful lot of people around out there who don't understand the concept of metaphor and how it works.

TR: Do you think it is one of the reasons you need to restrain your imagination when writing for adults? Is it a hindrance to work round, or is it useful allowing you to talk about things people would otherwise block off?

RH: I suppose there are occasions when it could be useful. I'm not sure it's a hindrance because people do it anyway, and books with the supernatural in it are enjoyed by people anyway. But if you want to be taken really seriously, its probably a hindrance because people have this natural tendency to think that if something is gritty realism it's automatically better and more serious, which from the author's point of view is certainly not true.

TR: Continuing along this line, about your other work, where is the strangest place your work has ever appeared?

RH: One that sticks in my mind as being the oddest is a very nasty crime story I wrote once --

TR: Dark and gritty?

RH: Oh yes; funny as well. I'll tell you the basis of the story; the main character is a petty criminal and mugger who mugs this guy, only the guy turns out to be a hit man for some underworld mob who's much more efficient at terror than the petty crim could ever be. So the petty crim finds himself under siege from this guy who nails his cat to the front door and kills his loved ones. And this appeared in 'Woman's Day'.

TR: 'Woman's Day' bought that! What year?

RH: Five or six years ago. The story had been written for an anthology of crime stories being published by Allen & Unwin. Now, they were very good at actually brokering deals with magazines so stories from their anthologies would first appear in magazines, and somehow they talked 'Woman's Day' into this.

There's an interesting aside to this story. Cat [Rob's partner] and I were at the Book Fair last year and we went for a cup of coffee and were just sitting around, and this woman came up and sat at the same table as us and Cat recognised her. She was the Fiction Editor for 'Woman's Day' and has been for decades. Now, anyone who reads 'Woman's Day' these days, the sort of stories that are in there are certainly nothing like that crime story, and I made reference to this fact, and said that she's published one of my stories once. She had no recollection of it. But it turned out that she had a year or two off and it was during that time it had been published!

TR: That was the Book Fair last year at Darling Harbour in Sydney?

RH: Yes.

TR: You attend a lot of these?

RH: I tend to go to the Book Fair just to see what's going on. They're getting smaller and smaller every year. When I first started going to them they were open to the public and were quite big, but now not even all the publishers attend. I guess they figure it's not worth it. I don't really know what the rationale is. But they run some interesting discussions; that year there was a discussion of the small press, things like that. I just wander around the publishers to get an idea, because they have samples of their latest stuff so you can see who's publishing what.

TR: I seem to recall you went touring around the place in regard to the 'Creepers' books. Has there been any such promotional activity for 'Shades'?

RH: I haven't toured; I've gone to a few things that I've organised myself but I don't really know what else is going to happen. The books were all written at once, and were all finished before they started to come out. They've appeared a month apart, which limits the sort of coverage they each get. With the last book out now, interest will pick up, hopefully. Hodder have done a lot of industry promotion, that is appearing in the appropriate journals and magazines and things, and there's been a reasonable number of reviews of the first book. But interest in YA genre fiction is generally low among journalists. No hooks!

TR: Can you say at this stage whether there are any further plans for the series, now that the four books are out?

RH: No, I'm afraid I can't.

TR: You've been very generous with your time, so I'd just like to ask you one more question. One of the first books you had published was a collection of short stories called Daydreaming on Company Time. That was in 1988. Is there any prospect of a further collection?

RH: Well, funny you should mention that because probably the next book of mine that will appear is called Immaterial and is a collection of ghost stories.

TR: A 'shade' away, perhaps?

RH: There are no 'Shades' stories in there but it is all related, and I think I was on a bit of a roll with ghosts and the themes that ghosts evoke in literature, which is coping with death and other issues of mortality (and how it affects our morality).

TR: So this is recent work?

RH: Some recent, some unpublished and some that have been published. It should be out almost any time from MirrorDanse Books.

TR: We're looking forward to it.

Sutherland, 14 October 2001

©2024 Go to top