Horror on Screen

INTERVIEWS

Lloyd Kaufman of Troma

ARTICLES

RELATED CONTENT

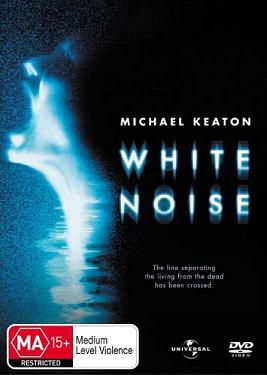

White Noise

Review by Robert Hood, 2005

"The line separating the living from the dead has been crossed".

Canada/UK/US, 2005

Director: Geoffrey Sax

Writer: Nial Johnson

Main cast: Michael Keaton, Chandra West, Deborah Kara Unger, Ian McNeice, Sarah Strange

Ghost stories often suggest a direct relationship with "real life", as an aid to suspension of disbelief; campfire tales and urban myths are dependent on such an appeal. In the past many ghost anthologies were made up entirely of anecdotal re-tellings of supposedly true experiences with the uncanny, and this has applied to the ghost film tradition as well, even though the best ghost movies (such as Robert Wise's The Haunting, Jack Clayton's The Innocents and Hideo Nakata's Ringu) are based on novels rather than real-life reminiscence. Films such as Stuart Rosenberg's The Amityville Horror and Sydney J. Furie's The Entity drew considerable publicity (if not narrative coherence) from their appeal to audiences' fascination with the possibility that depicted events might Really Have Happened. And more recently, Japan's horror renaissance has produced a series of anthology films under the title Tales of Terror from Tokyo and All Over Japan, made up of five-minute snippets directed by some of that country's "masters of horror". These stories are claimed to come from "the most horrifying of sources — The Truth" and are of necessity anecdotal.

Ghost stories often suggest a direct relationship with "real life", as an aid to suspension of disbelief; campfire tales and urban myths are dependent on such an appeal. In the past many ghost anthologies were made up entirely of anecdotal re-tellings of supposedly true experiences with the uncanny, and this has applied to the ghost film tradition as well, even though the best ghost movies (such as Robert Wise's The Haunting, Jack Clayton's The Innocents and Hideo Nakata's Ringu) are based on novels rather than real-life reminiscence. Films such as Stuart Rosenberg's The Amityville Horror and Sydney J. Furie's The Entity drew considerable publicity (if not narrative coherence) from their appeal to audiences' fascination with the possibility that depicted events might Really Have Happened. And more recently, Japan's horror renaissance has produced a series of anthology films under the title Tales of Terror from Tokyo and All Over Japan, made up of five-minute snippets directed by some of that country's "masters of horror". These stories are claimed to come from "the most horrifying of sources — The Truth" and are of necessity anecdotal.

While White Noise does not claim to be a true story, it does draw on the supposed reality of EVP or Electronic Voice Phenomenon to give itself credibility — and the DVD release of the film includes a raft of documentary information on the concept and those who actively research it. The film is framed by cards referring to EVP and we are given a brief rundown on it midstream by Raymond Price (Ian McNeice), a less-than-mysterious figure who has come to comfort main character Jonathan Rivers (Michael Keaton) with the knowledge that his dead wife may be trying to communicate with him, based on the evidence of messages received from Price's own dead son. This all suggests that the film's genesis lies in an interest in EVP. However, while EVP provides White Noise with its central motif and its basic plot drive, the film is not a docudrama in any sense. It is more than capable of surviving on its own dramatic merits rather than on an appeal to a disputed Truth.

In fact, I'm not at all convinced the film is well served by making any such obvious appeal to reality. At least one online commentator dismissed White Noise as New Age pap on the basis of EVP's comfortable message that our dead want to reassure us that they are alive and kicking in the afterlife. Ghost stories can, and often do, serve this purpose, carrying an implied (or upfront) assertion that death is, after all, not the End. Generally, though, the message is not an entirely comfortable one as the exigencies of the horror genre require a far darker menace to carry through the plot. But the message is there nevertheless.

To dismiss White Noise as EVP propaganda or cinematic comfort food would be a mistake, despite its own protestations. I admit the criticism of "New Age pap" seems justified at first, as Rivers becomes aware of EVP as a phenomenon and his scepticism is gradually eroded by the arrival of messages from his dead wife, novelist Anna Rivers (Chandra West). The comfort this brings in the face of his grief is undoubtedly a major source of his motivation to continue attempts at post-life communication. But the film contains a much more sinister thread that expands into a dark tapestry in the final Act, bringing about a climax that would surely not suit those who wish to promote EVP as grief therapy or those who look to the film for some kind of unalloyed emotional catharsis. The ending is, I found, somewhat grimmer and less comforting than might have been expected.

According to the director's commentary — and as witnessed by alternative cuts of several key scenes of violence included in the Extras section of the DVD — White Noise could have been darker still. These scenes were, however, re-edited to ensure its PG-13 rating (M in Australia). The subtler horror that results takes little from the film's impact, however, and might arguably enhance it. This isn't "splatter" horror and does not aim to be. The first of these scenes — which is also the first on-screen violence — carries enough impact as it is, being largely unexpected and affecting a character for whom we have developed alternative expectations. Still, scenes of torture in the climax would perhaps have gained in clarity if the cuts there had not been made.

According to the director's commentary — and as witnessed by alternative cuts of several key scenes of violence included in the Extras section of the DVD — White Noise could have been darker still. These scenes were, however, re-edited to ensure its PG-13 rating (M in Australia). The subtler horror that results takes little from the film's impact, however, and might arguably enhance it. This isn't "splatter" horror and does not aim to be. The first of these scenes — which is also the first on-screen violence — carries enough impact as it is, being largely unexpected and affecting a character for whom we have developed alternative expectations. Still, scenes of torture in the climax would perhaps have gained in clarity if the cuts there had not been made.

Another thing this film does not offer is typical blockbuster spectacle. Much of its effectiveness lies in its personal drama and atmosphere. Indeed the somewhat clichéd opening, which requires the death of Anna Rivers, is handled with effective restraint by director Sax, downplayed and seen totally from the perspective of Keaton's architect protagonist. It succeeds in involving the audience in a way that a more upfront approach, carrying a heavier load of cliché, would not have done. Drawing on scenes of idealised domestic bliss — including the revelation that Anna is pregnant — the indirect approach to these elements of the narrative create a powerful emotional background against which small moments of supernatural intrusion (such as a cell-phone call from Anna's own phone, which is not switched on, or a voicemail message where there is no message recorded) can carry a startling frisson — and more readily lead to bigger things.

This is director Geoffrey Sax's first cinema feature, his previous work being on TV series and, most conspicuously, on the not-entirely-well-received Dr Who: The Movie (1996). His control of the narrative, though straightforward, is sure and visual techniques such as the use of high-angle shots reminiscent of Wise's The Haunting (which suggest something outside looking in and often isolate Keaton within a vast dark environment) create an aura of unease. There is a built-up of anticipation that, while somewhat predictable, effectively involves the audience and culminates in a climactic sequence that might be criticised as a touch overt but that works regardless. The use of background noise throughout the film, too, serves to unnerve. Noise is central to the storyline, of course, which deals with the condensation of meaningful words and images out of meaningless sound and vision. As described in one of the DVD extras, EVP works through a "thickening of available background noise", as though the spirits of the dead need unused sound, and visual information, in order to form a tenuous link to the living world. How this works in relation to an actual physical manifestation of the more malign entities we are eventually presented with, I don't know, but it made enough quasi-sense to carry me along for the ride. Intrusions of indistinct word-patterns into meaningless noise-scapes and vague images into the visual fog of an unfocussed TV screen often give quite a jolt.

It was good to see Keaton at work, even though his performance is rather more restrained and naturalistic than we've come to expect from his classic turns as Beetlejuice and Batman. A suggestion of these characters is evident in a certain welcome humour that he injects into his performance as well as a darker intensity reminiscent of the tormented hero of Gotham City. At any rate he gives a professional performance that enhances the narrative rather than works against it — which is not something that can be taken for granted these days.

In the end, like the messages of its spirits, White Noise does manage to coalesce background static into something meaningful — a decent ghost movie, in fact. While not as inherently dazzling as, say, recent Japanese contributions to the ghost-film tradition, it is a welcome addition to the genre and certainly worth a look.

©2020 Go to top