Australian Comics

COVER GALLERY

A History of the scene

Adventures of Andy in Comicland

Tale-Trader The Legend of Twarin

The Tiger Who Wanted to be Human

INTERVIEWS

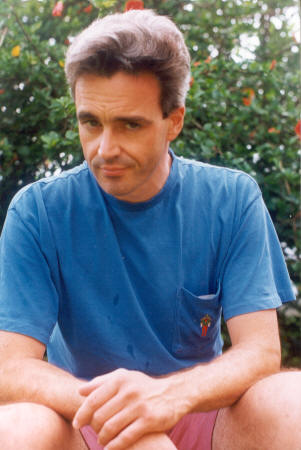

Eddie Campbell

REVIEWS

OTHER

Hellblazers Delano and Ennis

EC Comics

An Interview with Eddie Campbell

by David Carroll

First Appeared in Tabula Rasa#4, 1994

I first encountered Eddie Campbell's stark and expressive style in the comic From Hell, a superb and richly detailed look at the Jack the Ripper case and all that surrounds it. Indeed the writer, Alan Moore of Watchmen, V For Vendetta and The Killing Joke (just about the most dynamic force in comic writing in its current era) points out that the art is perhaps better researched than the text itself. Next I find out that he is the upcoming writer for Hellblazer, one of my favourite comics that has fallen on lean times of late. Ah, say I, a horror fan if there ever was one. But probing deeper I found the Deadface comics, the adventures (and I use the term loosely) of the god Bacchus, and then a series of vignettes on everyday life called Alec. So like every artist who refuses to be classified, there is more to meet the eye. But let's find out what he thinks about our favourite subject...

I first encountered Eddie Campbell's stark and expressive style in the comic From Hell, a superb and richly detailed look at the Jack the Ripper case and all that surrounds it. Indeed the writer, Alan Moore of Watchmen, V For Vendetta and The Killing Joke (just about the most dynamic force in comic writing in its current era) points out that the art is perhaps better researched than the text itself. Next I find out that he is the upcoming writer for Hellblazer, one of my favourite comics that has fallen on lean times of late. Ah, say I, a horror fan if there ever was one. But probing deeper I found the Deadface comics, the adventures (and I use the term loosely) of the god Bacchus, and then a series of vignettes on everyday life called Alec. So like every artist who refuses to be classified, there is more to meet the eye. But let's find out what he thinks about our favourite subject...

Eddie Campbell: I thought about this, I thought these people are ringing me about horror. I don't think I like horror, I don't think I'm interested in horror. I have problems with the Hellblazer thing... I'm only doing four issues of that. We were banging our heads over it, agreeing it isn't really 'in character'. I'm happy with it, the four issues I've done -- or at least I'm writing the third one now. But the trouble with the whole formula thing, because it's horror, because it's Hellblazer, because it's John Constantine, there has to be exactly five and a half ounces of nastiness per issue.

Tabula Rasa: Does there have to be? With Garth Ennis there certainly is.

EC: Yeah. They're weighing it. They get my script and they weigh the nastiness and if it comes in an ounce short I've got to rewrite, I've got to add something in. I mean that Constantine himself has to exude nastiness. It's certainly an unusual book. There is no other like it.

TR: Is that editorial or reader expectation?

EC: Well, they've been selling it for eighty issues and they know what sells it. It's Vertigo's second best seller after Sandman. I don't think they like this horror connotation as a description of the whole Vertigo line. I was at the convention in Glasgow, and they were searching round for something they were happier with, and they were happy with 'Dark Fantasy' as a catch-all for what Vertigo is about. To me it's still horror, and I don't actually like horror. I mean the 'horror story' as manipulative entertainment. I'm not saying that if there is something horrible in the world we shouldn't draw attention to it... hide my head under the carpet like a big ostrich.

TR: There seems to be some dissatisfaction at Ennis' 'in your face' style and a desire to return to Delano's subtler, if still really nasty, methods.

EC: All that political stuff Delano was doing. Me, I've gone off the top, into total fantasy. They're seemed to be some perception when I came on that I was bringing it down to earth a bit more, but I've done totally the opposite.

TR: Reading the Deadface comics, they're very down-to-earth. I think the quintessential image was the Minotaur wearing the smoking jacket, Joe Theseus and so on. Is that the opposite of what you're doing in this?

EC: I can't really be myself on Hellblazer. I was asking Neil Gaiman before I got on to it and I said I don't think I can do it. They rang up to ask if I could write it -- Lou Stathis was editing Reflex Magazine about a year and a half ago and that went out of business. I used to write a column in there, called Genius, And How It Got That Way, they had asked me to write a column on the great comics in history. I thought, well I can do that. I couldn't be bothered writing a book review, because I'd have to read the book, I haven't got time to read a whole book for a fifty dollar write-up. So I wrote about the geniuses of the comic strip, Segar, Kurtzman, Will Eisner and Jules Feiffer were the ones I did, although the last one didn't appear, the magazine went bust and I didn't get paid for the last one. So Lou was out of a job and he landed at DC, with Vertigo.

TR: Was this in Britain?

EC: Reflex was a New York magazine. It was a Rock/Culture 'zine. They had a section on comics, three pages at the back. So that's my connection. Lou needed a writer since Garth was leaving Hellblazer at issue 83 and I think Lou decided to have a complete sweep clean. New cover artist, new writer, new artist, everything.

TR: Who's the artist on it?

EC: The artist is Sean Philips. But what happened was that we ended up taking so long to agree on what the hell we were doing. I did a synopsis and everybody was happy with it, but when I came to do the script they got it in and they weighed it and there was only two ounces of nastiness. It was taking so long to get it just so that they got Jamie Delano to do a fill-in issue, which is appearing as number 84, and I'm doing 85 to 88. So I had to come up with another three ounces of nastiness. Jamie's fill-in is brilliant, by the way. Two and a half kilos of undiluted evil.

TR: Do you think you could write something else for Vertigo that didn't have this big history behind it?

EC: I don't think I'm entirely in tune with the Vertigo house style at this juncture, but I'm thinking about it.

TR: Is that to do with its British domination and thus entirely pessimistic outlook?

EC: They've got this house style which is writer driven. I heard of one person who sent his script in, and Karen [Berger] said there weren't enough words in it. Put some more in.

TR: She does seem to have a well-defined idea of what's going in.

EC: She's done well. It's business, selling comics, you work out what sells and you don't want to muck about with it too much. I'm going to publish Deadface on my own, that's what I'm going to do. I'm going to republish all the stuff that's out of print and new stuff in there as well. In the first issue I've got a Bacchus and Cerebus crossover. I was locked up in a hotel suite for five days with Dave Sim and we've done the crossover.

TR: So is there going to be a mega-crossover and Cerebus is going to meet Bacchus?

EC: Bacchus has already appeared in Cerebus, way back in November '91. He had this crowd of people throwing bottles and Bacchus was in there. The new one is a lightweight, humorous thing. But we worked hard on it. It was a lot of fun -- all five pages of it.

TR: If you're publishing Deadface on your own, does that mean Dark Horse is dropping it?

EC: No, no, I do stuff with Dark Horse. We've got a miniseries coming up called Hermes versus the Eyeball Kid, and we've got the Bacchus Colour Special and, talking about horror, I'm doing The Picture of Doreen Gray, which is all about face transplants. She's a film star and has hired The Body Corporation to find the perfect face for her. But she keeps getting these faces and none of them are taking, they're all rotting. She thinks you can just hang it on your skull. That's six issues in Dark Horse Presents. Doreen Gray, the last word on face transplants. Issues 93-98, with a couple of covers too in there.

TR: And you've got From Hell. Is that going well?

EC: I'm currently just working on the new chapter which is fifty pages of Gull cutting up Marie Kelly. It's not the last one. Five's out, six is coming out in November, that's a single chapter, and then seven is the big horrifying one. And I think a couple after that to wrap the thing up.

Everything that's happened before suddenly acquires a significance, all that stuff about the architecture -- when the knife is going into the heart cavity, we follow the knife in and we rush down through the capillaries, veins and whatnot, and we're inside this enormous meat cathedral, and he saws off one of her breasts and puts it on the bedside table and that's the Dome of St Pauls.

TR: Making five pointed stars and the like?

EC: I'm just drawing it now. It's totally revolting. I'm sure you'll love it.

TR: So how did it all come about? Alan goes on about the amount of research you have done for the project, so was it a prior interest?

EC: The story goes, Alan came up with it for Taboo. That was when all these guys decided they would self-publish, and I don't think any of them, Bissette and Moore (who did Swamp Thing together for four years), had any business sense. Because Taboo was supposed to be a quarterly magazine and it came out once a year. We had this bloody running serial in there that was supposed to be eight pages a chapter, and the first chapter was eight pages, and the second one was twelve and the third one was nineteen and the fourth was thirty-two and the fifth one was forty. The one I've just finished is fifty-eight. He just gets longer and longer, more and more long-winded.

TR: Is it just all the research coming out?

EC: He just keeps expanding, I've just spent three pictures of someone hitching up his trousers before crouching down. It just takes more and more pictures. In the old days a guy could scratch his bum in one picture, and under the new regime it takes five pictures to scratch your bum.

TR: He's obviously got a good idea of where's he's going.

EC: Oh yeah, he's very organised. In his head he's very organised, in his day to day life it's a total disaster area. Well, to an organised guy like me. I have to do two pages of book-keeping to go round the corner for a newspaper. Seriously.

I did this thing called The Pyjama Girl. Have you heard about the Pyjama Girl? It was a girl who had been bashed in the head with a blunt instrument on one side and shot through the other and was totally unrecognisable. This was in 1931. They kept her body in a bath of preserving fluid in Sydney University for ten or eleven years and she became almost a tourist attraction. She was on view for somebody to come and recognise her. Anyone who made the trip to Sydney had to see the Pyjama Girl, just out of morbid curiosity. In the end the University complained and she was taken away to the morgue. You had to make an appointment to see her. But it was just a crazy spectacle, people filing past. The horror idea in that, as Bissette noted in his introduction, the rather disturbing idea that we could be killed and we'd be so forgotten that the next day nobody would recognise us. We could hang around for ten years and nobody would care enough to identify us. Therein lies the horror.

So Alan was writing and Steve Bissette was editing Taboo and they needed an artist that wouldn't be carried away by the glamour of violence. The point behind From Hell is, I think, a feminist point. It's all about the horror inflicted by a patriarchal system, that's Alan Moore's basic theme. Because in his philosophical flights of fancy in the fourth chapter, Gull is calling upon all these mythical precedents where Goddesses have been suppressed in one way or another. He cites the history of man and woman from a feminist viewpoint, but he puts it in the mouth of someone who wants to usurp that, who wants to re-establish the old order, which is an interesting trick. I tried a similar thing, taking Alan's cue, in one of the Deadface things, I had the God of Capitalism, Chryson, describe the history of capitalism from the point of view of a socialist critique, but because it was in the speech of the guy who was going to re-establish the domination, there was something wickedly evil about it, which is exactly what Alan did. It was a rather icky and slightly insidious trick to play, I thought. It intensified the villainy of it, because it's a knowing villainy. The villain isn't a victim of the system, the villain is above all the system but he's going to do it anyway.

TR: So where does Queen Victoria fit in?

EC: I remember having an argument with Alan, I said the Queen's not just going to call the guy up and send him out to do it. And Alan says, well, how would a monarch give orders to her assassin. When Alan is totally intent on an idea -- and Alan lives and writes in the realm of ideas -- he seems to be oblivious to the nuts and bolts. I think the actual pecking order is such that the person in power doesn't give the order to go and kill this guy. What was the Shakespeare thing? Will no-one rid me of this meddling priest? So the guy within earshot does it, goes out and kills the guy. And I think in the corridors of power these dangerous kinds of orders are issued in a much more vague way, passed down two or three levels of command before they're given to the assassin. To me it just didn't ring true the idea of Queen Victoria calling Gull in and saying go and get rid of these women. That was the bone of contention.

TR: So the writer wins?

EC: I would have thought it'd be a lot more complicated than that. Victorian sense of duty is a powerful motivating factor. I sent Alan an article on this. Everyone involved in this would have a slightly different position on this ladder of duty, even down to Abberline, the cop, though he's a grumbling, grouchy bastard. He would still see it as his duty to shut up and get on with it, not cause any trouble. In our own time we've made a hero of the rebel, and it's more heroic to speak up. Part of the problem I think is that neither Alan or myself can get entirely into that Victorian mindset, to use a modern word. I'm aware enough of the problem to know we haven't solved it. It's a twentieth century book, written from a twentieth century perspective. A lot of the stuff that Gull comes out with, it's arguable whether a guy in 1888 could have access to that information. None of the archaeological digs had been properly written up at that time, they had happened, but they hadn't been properly analysed and published. [Heinrich] Schlieman was still digging up Troy, Alan refers to that. It was happening at the time and it's part of the whole picture, so let's use it.

TR: It's certainly taken a while.

EC: Yeah. It's the whole Taboo thing, there was no point getting too far ahead, because Taboo could only pay us up to a certain point. But now we're striding forward -- you saw the last one issue of From Hell?

TR: Number five?

EC: Yeah, I was really excited about that one. It's taken me a long time just to be perfectly happy with the artwork, the last one I was really pleased with, where he's got William Morris reciting his poem Love is Enough while the murder is being committed in the alleyway below.

TR: You read the comic, and then you read the appendix, and you go yes, there was a picture of Karl Marx in this room...

EC: There again, I don't know. The more I investigate the thing historically the more unconfident I've become about the whole thing being accurate. But then, does it matter? It's a work of fiction. It's a novel. It's Alan's novel. And on its own terms it works.

TR: It is certainly conveyed well. Alan has picked up on all these details like there were grape stems here and it all seems to point to this huge conspiracy.

EC: Yeah. The most interesting thing about Gull he hasn't been able to work in, something I dug up. I was investigating a completely separate thing... anorexia nervosa, and apparently it was William Gull who gave the name to anorexia nervosa. There was a guy in Paris who was writing a paper at the same time on it and he'd managed to pin-point the thing as an independent illness, but I think it was Gull who took the initiative in seeing it as a psychological thing. So all the time I'm drawing Gull I was thinking he was sort of this forgotten character, I can't even find him in my encyclopedia here. I've got this Encyclopedia published in the 1930s, it's useful to me because it's got all these English gentlemen who are now totally forgotten, and pictures of them, very useful, but Gull's not in there. So I'm thinking has Gull done anything of relevance to our times. I was just investigating something totally separate and discovered by accident that Gull is the man who wrote the paper that gave the name to anorexia nervosa. Not only that but I think he did it in 1888. It was in the eighties... I've sent all the bloody notes to Alan. But his special interest was treating women's problems with hysteria. We forget that the word hysteria comes from the Greek for uterus, ustera, as in hysterectomy, so the word hysteria actually refers specifically to the area of women's disorders. I'd be interested to read Gull's paper on it, and I wish Alan would put it in somewhere. It gives him a relevance to our times, which he doesn't otherwise have. Gull, I mean, not Alan.

TR: What about your own writing? What's the difference between writing comics and drawing them?

EC: I'll tell you what. Something I've realised is that I don't enjoy writing for other people. I've just done the new Sandman gallery, The Gallery of Dreams, remember they did the Death gallery? I did a painting for this, and everybody's thoroughly happy with it. They're exhibiting all the pictures in a New York gallery and the gallery phoned me up and they're happy with it, it's their favourite picture, they say. I'm thinking to myself, I just love doing the art, it takes me a morning to do... I love doing these paintings. But every time I'm in demand to do something they phone me up and want me to write. I just wrote, about a year ago, this bloody superhero thing for Dark Horse... The biggest disaster of my scrawny career so far. They asked me to write it and zoomed me over there to do it. But they ended up sacking me. I wrote five issues of that and got the sack. Actually, they paid me for eight, but they changed their minds about the direction and threw three issues out the window.

TR: Is that because writers are in demand?

EC: I don't know. They've got this clear idea of what they want, and then I write something else. I think why don't they bloody write it themselves if they're that clear on what they wanted. What did they think I was going to do? I'd be interested to see what happens to this Hellblazer thing. It's totally wacky, it's so totally nothing to do with Hellblazer that it could almost become a cult hit or something. I don't know. It's the maddest thing I've ever written.

TR: Jamie Delano did one-offs that were pretty weird, like Winnie the Pooh dragging the writer down to hell...

EC: I didn't like that, it didn't work. I found going that far into whimsy didn't work for Hellblazer.

TR: So this is different again?

EC: Yeah. You'll have to see it. It's all insane, reality is coming unstuck. Reality has been undermined by a virus... Introducing disorder into an orderly system, with a supernatural aspect to it. But I keep coming in underweight, can never get that five and a half ounces of nastiness.

TR: You say you're self-publishing. Are you going to continuing writing...

EC: I don't know. I don't want to write, I'd rather draw. In the last year I put out two books, Graffiti Kitchen and The Dance of Lifey Death. These are the best things I've ever done. In a perfect world I'd like to do just that kind of stuff.

Graffiti Kitchen is published by Kitchen Sink, it's a forty eight page love story. It's quite cheap, $2.95, which was horribly underpriced, they made a loss on it. They're about real life, these books, both like novel length things. There's another book I did last year, A Thousand and One Nights of Bacchus. There are a couple of things in there if we're constraining this discussion to horror here. There a story in there which is a take on Dostoievsky's Bobok, about this guy who gets drunk and wakes up in a graveyard, and he hears the voices underground, a nine page story about this guy listening to the dead talking to themselves. A Thousand and One Nights of Bacchus has five short stories in it, but this is always everybody's favourite. I modernised it, gave it a couple of modern twists. In fact it's got nothing to do with Dostoievsky, I just stole his idea. There's another story in there I'm happy with, The Testament of the Angel Seamus. Those are the things I'm happy with.

From Hell's alright, it's Alan's book, I'm just illustrating it, it comes in as always horrifying, I try to take the horror out of it, try to play this real deadpan... it kind of works, actually. They just produced a book of Alan's scripts, in a ninety dollar hardback, I did some spot illustrations for it, but it's really interesting to read because Alan's one of the most interesting writers in comics. In an Alan Moore script he describes it, his prose is unbelievable. Any other writer of comics says 'in this panel it is raining'. But Alan says 'the rain beats out in staccato morse code the rhythms of a dreary Russian novel'.

TR: And you look at that and go, it's raining...

EC: It's raining. I make it rain. But Alan's scripts do that all the time, they're just so dense with poetic metaphor, they're a great read, and none of it ever gets on to the page. It's just for my benefit, to help me visualise the picture. That's a book worth checking out for anybody who's interested in From Hell, or Jack the Ripper generally. I think they'll put it out as a paperback later on... It's expensive. It's a lovely book, by Borderlands Press. For insights into the workings of a unique mind... see where it all comes from.

TR: On a more practical note, how did you break into the market?

EC: I've been in comics since about '81. For the first couple of years I was small press, printing them myself, Escape magazine, print runs of two or three hundred. I think we did as many as five hundred sometimes, just photocopying books. By '84 we did a thousand copies of the first Alec book with a laminated cover and everything, a really nicely printed book, and we lugged that round the place, through all the different systems we could sell it. '85 I did another one. '86 I did another one. In the meantime since '84 I'd been in the rock magazine Sounds every week for two years. It was a comic strip, going right across the tabloid page. Then we set up an operation, I don't know if you've heard of Harrier Comics, it was me and Glenn Dakin and Phil Elliot, we used Harrier's distribution system and set up our own operation, called ourselves Harrier New Wave. In a two year period we put out about thirty six comics. With Harrier these were like American black and white comics. There was this big boom for black and white comics -- this was when the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles came out. This thing was such an enormous hit that everybody was behind these things, looking for the next enormous hit. You could just print any old black and white shit and sell twenty thousand of them, it sounds totally unbelievable now. The thing was everybody looked at it and said I've gotta get in there, so naturally three million people try to get in and the bottom fell out. I came in on the decline. Phil Elliot was in first, he got his book out, he sold thirteen thousand, I think he got two issues out before I got mine in, this was March '87. He was out in December '86. By March '87 we're down to seven thousand, by the end of the year we're down to twelve hundred. The whole bottom just fell out of the market. It was bad for me because I was in Australia at the time. I thought all I have to do is send it in and I could travel the world, everything went wrong, and I was stuck over here, 'cause I was starting to have children... it was a disastrous time. I did about twelve books in two years. We were just publishing them ourselves, the whole black and white boom thing was just a license to print money, you could print any old rubbish and it'd sell.

Because of the Mutant Turtles, you know? They were black and white comics, so suddenly people wanted black and white comics, without thinking that things sold because they've got some integral quality about them that makes them desirable. The retail mentality is, they look at the outward appearance of the thing. The Turtles wasn't a well-drawn or well-written comic, so what was it that captured people's imagination about it? Retailers just thought 'Amateurish crap is selling, quick, buy amateurish crap!' They failed to see there was something that caught people's imagination... And when you look at the Turtle's movie there is something there, definitely something there. So I had all these Harrier comics that I'd done on a smallish scale and I used to send them in to Dark Horse, because Dark Horse were the only publisher that had ridden over that slump, and in '89 they were doing really well. All the others, like Renegade, they'd all fallen down, Fantagraphics had lost a lot of ground. I'd been in Fantagraphics Magazines, like Prime Cuts, from about '86 onwards, I'd been in some American publications. I just took Deadface down to Dark Horse and said this thing's gone well... I just need someone to publish it, so I kind of self-published it, then I got Dark Horse interested. You've got to build these things up. I did twelve bloody comics, I think most people start and give up long before... you've got to be so totally mad you don't realise... Dave Sim said in his latest thing of his, 'when you're on the right track, you'll know it, but until you get there, you have to believe you're on the right track'. Interesting little conundrum. It's not easy... There's so much stuff out there.

TR: And finally, if they made the Aliens Versus Deadface movie, who is going to play Bacchus?

EC: Somebody said to me once, Willem Dafoe, and I thought about it. I thought, yeah. Yeah.

TR: Thank you very much for your time, and good luck in the future.

©2011 Go to top