Doctor Who

Articles

BOX OF JHANA

OTHER ARTICLES

REVIEWS

K9 and Company novel

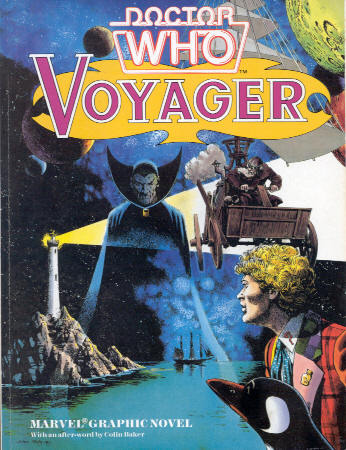

Doctor Who: Voyager

Doctor Who: Voyager (again)

RELATED CONTENT

Doctor Who: Voyager

Reviewed by David Carroll

Doctor Who Magazine issues 88-99, script by Steve Parkhouse, art by John Ridgway, 1984.

Doctor Who Magazine issues 88-99, script by Steve Parkhouse, art by John Ridgway, 1984.

I don't know, it may have been something in the water. It may have been that the Eighties were a point where you got the generation growing up and starting to write, early twenties and so forth, who'd grown up with Doctor Who...Neil Gaiman

In a real sense the comic strip in Marvel's Doctor Who Magazine (nee Monthly, nee Weekly) was quite an important entity in itself, separate even from the TV program that it drew from. It was the original impetus for the magazine itself, started in 1979 when Marvel brought the rights for the comic series from Mighty TV Comic. The idea of these regular stories being combined with a magazine format was judged feasible by previous efforts with that other bastion of British culture, House of Hammer, and its success has been obvious. But more than that, the comic was there, at a time when an awful lot of talented Brits were entering the field of SF, fantasy and horror. Perhaps even stranger than this sudden insurge of weird ideas (nothing had been seen like it since the Order of the Golden Dawn late last century, but that's a completely different story) was that the moribund field of comics was seen, by the artists at least, as a viable means of presenting these ideas. It took a long time for this to be taken seriously, and whilst the 2000AD title (think Judge Dredd) was the vehicle that finally provided the stability needed in the industry, the Doctor Who comic was definitely there for the long term, helping things along.

If you know something of the British comic industry (which receives widest circulation in the on-going Vertigo imprint from DC -- who rather sensibly stole the talent right from under Marvel's nose), it reads like a Who's Who (so to speak). Grant Morrison, Alan Grant and Jamie Delano have all written for the strip. The phenomenal intellect of Alan Moore had been turned to a story with Sontarans in it, and Dave Gibbons, Moore's collaborator on Watchmen, was with DWM from the beginning. John Ridgeway, who provided the definitive look for Hellblazer's John Constantine, and Steve Parkhouse, who has drawn individual issues of everything from Sandman to The Invisibles also had their stints (incidentally, Neil Gaiman hasn't worked on it -- he's been more involved with the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy). Providing an indication of the influence these sort of people have had on the modern genre would be exhausting, but it is both significant and wide-ranging. And to make it all completely incestuous, Andrew Cartmel has stated the British comics of the 1980s were a big source of inspiration for his brand of Doctor Who. The 2000AD story The Ballad of Halo Jones by Alan Moore he mentions in particular -- the story of a young woman who would do anything do get off the overcrowded earth, from becoming a waitress to joining the army. Ace!

So with all of this talent passing through the series, does it mean that the Doctor Who comic was a showground of excellence? Unfortunately, it ain't necessary so...

To give an idea of what could be achieved, and perhaps shed some light on why this potential was not always realised, let's look at one of the most successful of the stories, or more precisely the 12 issues worth of interconnected weirdness later coloured and reprinted in one volume, Voyager.

Steve Parkhouse had written the comic throughout the Davison years and continued well into the Colin Baker era. Though later better known for his artwork, he provided some excellent story arcs during his stint. He was also not one of those that had grown up with the good Doctor -- he is reported as commenting: 'I perceived the program as juvenile entertainment, where almost-famous actors delivered third-rate lines whilst avoiding the wobbly scenery'. Doing artistic duty was John Ridgway, whose opinions of the TV show remain unknown to me, but who still illustrates the occasional story within the magazine (and a favourite of mine, besides). The story itself revolves around our hero's encounters with the famed Astrolabus, as they are both pursued through time by the mysterious Voyager, whose name was death. In between the Doctor fixes up some old debts with the evil Mister Dogbolter, kidnaps the eminent Dr Ivan Asimoff, and joins forces with the redoubtable Frobisher, private eye and, for personal reasons, penguin.

It's all wonderful stuff and, as you may imagine from this run down, it doesn't owe a lot to the details of its source. Make no mistake, it is Doctor Who -- Time Lord history is mixed up in the plot, and both the TARDIS and the Doctor himself are as they should be (Steve does a slightly mellower but nonetheless well-realised Sixth Doctor). More importantly, it has a lot of the soul of the program at its best -- using science fiction as a less than rigid framework, presenting grand ideas with a real sense of wonder, and a lot of humour besides. But it is a different type of story than Doctor Who would attempt on the screen -- not so much style over substance, but using style to justify scenes that resonate more emotionally that 'realistically'. Frobisher himself is a perfect example of how and why this works so well. A sleuth on the mean streets of the future (real name Avan Tarklu, or is that just another alias?), he seems a romantic and even naïve soul. Whilst later writers would have problems fitting a character able to shapeshift at will (even into functional technology, it seems) into their plots, it is all just part of Voyager's tapestry. Whilst not without the odd clumsier moment, its story and audacity carries it almost effortlessly.

Voyager was the last of Steve Parkhouse's efforts on the magazine. He had previously replaced the long running writer Steve Moore, and was himself replaced by Alan McKenzie (writing as Max Stockbridge) for another twelve issues. After that the comic strip was allocated to writers for individual stories, allowing them to tap that large pool of talent I mentioned earlier. At the same time more elements of the actual show were being used, Peri and occasional past companions, plus familiar monsters and locations. In short, it became fannish, a situation continuing to this day.

As part of the magazine that may have been a good thing -- for the comic itself, maybe not. I don't think it a complete coincidence that Steve Moore, the writer before Steve Parkhouse, shared his attitude to the show, say it 'induced feelings of monumental indifference in me'. But before we are too quick to condemn fan exuberance, there is another factor or two to remember. Firstly, choosing to go the route of rapidly changing writers means you need to use the show's continuity, just to provide some sense of consistency. To my mind, that kind of background is just not sufficient when it comes to an on-going comic series, certainly not without very careful editing indeed. The same methodology with other subject matter (Vertigo's The Dreaming comes to mind) has had similar results.

The second point is that British writers and artists of the 1980s were creating a different type of comic, for a different audience. The other story arc DWM had most success with during that time was Abslom Daak, Dalek Killer. This certainly did use Doctor Who mythology, but reinvented it with a Judge Dredd mentality. It would take the TV program another five years or so to reflect the dark, deconstructive and social-conscious fantasy that was the mood of the times. It was when the comic had the time and willingness to break that new ground, even at the cost of familiar conventions, that its potential became realised. That it became most worthy in its own right, a part of both Doctor Who and the larger field to which it is related.

Notes

Some details in this review were taken from Michael Bonner's article Strip in DWM issues 154 and 155. The Neil Gaiman quote is from an interview by myself, first published in Bloodsongs Magazine, issue 8 and now on-line. For a more personal look at the development of the comic industry during the time in question, see Eddie Campbell's Alec: how to be an artist. DWM doesn't get a mention, I'm afraid.

©2011 Go to top