MirrorDanse

MIRRORDANSE BOOKS

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 1, 2004

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 2, 2005

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 3, 2006

Year's Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 4, 2007

MIRRORDANSE EDITIONS

OTHER BOOKS

SAMPLE STORIES

Cigarettes and Roses, by Ben Peek

The Desertion of Corporal Perkins, by Bill Congreve

The Hours Before Sunrise, by Bill Congreve

The Mullet that Screwed John West, by Bill Congreve

RESOURCES

2005 short fiction (pdf)

2006 short fiction (pdf)

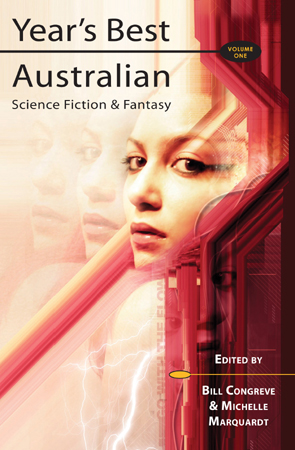

The Year's Best Australian SF & Fantasy, One

Edited by Bill Congreve & Michelle Marquardt

Paperback 195 mm x 128 mm (73/4 in x 5 in), 255 pages.

Paperback 195 mm x 128 mm (73/4 in x 5 in), 255 pages.

ISBN 0-9757736-0-7

RRP $19.95 (inc GST)

(Published September 2005)

Introduction

The kangaroo peered over the crest of the sand dune at the invaders. Little wooden boats with little flags fluttering in the breeze carried little white men to shore. And the little white men wore silly red and white uniforms that he could have seen kilohops away, even if he hadn't smelled them first. The didn't just look like they had spent six months on a ship, they smelled like it, ripe and rancid. They wouldn't be as tasty as the goanna the roo had eaten for breakfast, but it was going to find out. It shifted the AK-47 in its paws, and pulled a hand grenade from its belt.

The wooden boats looked silly. All sails and things. No steam, no diesel. And who did they think they were going to scare with those ancient muskets?

Where had these idiots come from? But that wouldn't matter, as long as they were tasty ...

#

The popular fiction genres, such as romance, fantasy and crime, are only twenty years old in Australian mass market publishing, at least in the current incarnation. There was an earlier boom in Australian speculative fiction, largely caused by WW2 and the import restrictions on pulps from England and the US. The result in those decades was a flourishing pulp fiction industry in all genres: SF, Romance, Crime, Horror, War Stories, etc. That boom died away in the 1950s. Parts of it hung on until the 1970s, such as the publishing house Horwitz with J. E. MacDonnell's novels of naval adventure. Then Australia was left with publishing programs in literary and children's fiction, both supported by government grants, but little else. Popular fiction became the preserve of multinational corporations importing books printed and published in the UK.

The break-through book for the re-establishment of an Australian popular fiction industry came in 1983. It was a crime novel, and not anything to do with SF at all. That book was The Empty Beach, by Peter Corris (who is still active in crime fiction), and it had to be published by an independent textbook publisher in order to see the light of day. Why a textbook publisher? Well, the mainstream publishing industry has always been conservative and unused to risk-taking (still its greatest drawback in this country), and the popular fiction distributors of the time were all UK companies.

Even now the majority of Australia's larger publishers are multi-nationals. A book published in Australia was one less book that could be exported from the UK by the parent company. If the Australian subsidiary published mass market fiction, it would be competing with its parent company, and that competition wasn't allowed. Even in the late 1980s, Australian publishers were being told by their English superiors not to publish popular fiction.

Despite proven sales figures, local popular fiction publishing took time to build momentum. Crime writing led the way, followed by other forms of fiction, including fantasy. The early leader in fantasy publishing was Pan Macmillan, with such authors as Martin Middleton, Shannah Jay, and Graham Hague. That first surge died away, due largely to derivative, poor quality fiction. The inexperience of the publishers with genre fiction showed. In the speculative genres, and with the notable exception of generic high fantasy -- imitations of Tolkien, Eddings and Feist -- that inexperience continues to this day.

#

The leader of the little white men marched up the beach and tripped, falling onto its hands and knees. With some assistance from the others it struggled back to its feet and brushed sand from its dress uniform. It pulled a scroll from its pocket and held it high. "I claim this land in the name of ..."

The kangaroo had a family to feed. And these idiots were just too silly to live.

It was now or never! Tasty or not tasty. She loves me, she loves me not ...

He stood to his full four metre height and aimed.

#

There is very little science fiction or horror published by the multinationals in Australia. Most of what they do publish is reprinted from US or English editions, a comforting proof that the book already has an international track record. The majority of Australia's best known science fiction writers, Greg Egan, Damien Broderick, Sean Williams, Sean McMullen, Shane Dix, are published internationally. These authors then have their international editions imported into Australia.

Why are the major publishers only interested in fantasy? If a fantasy novel sells 5000 copies, and a science fiction novel sells 3000 copies, a major publisher will publish the fantasy novel. Both will make money, but in a marginal market place niche marketing is ruled out by the bean counters who have invaded much of the role editors once held. The lower selling genre is sacrificed. Horror? Well most story-telling in any genre of fiction contains a degree of horror. Call it crime, call it drama, call it literature, call it young adult, and that's okay. Call it horror and the old stigmas and prejudices surface. Local writers interested in anything other than generic high fantasy must remain in the independent presses, or seek publication.

The dominance of fantasy in Australian genre publishing is such that Jennifer Fallon's recent Second Suns trilogy, which is SF in the vein of Anne McCaffrey's Pern novels, or Marion Zimmer Bradley's Darkover books, was published and marketed purely as fantasy by Harper Collins.

But with fantasy, the overseas publishing phenomenon has worked in the other direction. The best Australian authors were published locally first, and then had their work sold overseas. The best known, Garth Nix, Sara Douglass, Juliet Marillier, Kate Forsyth and Ian Irvine, are becoming household names, perhaps because all are telling their own stories, and finding their own direction out of the generic morass. Here are a few more names international readers will discover on their shelves: Tony Shillitoe, Glenda Larke, Simon Brown, Jennifer Fallon and Trudi Canavan. But what seems derivative to an Australian audience can be fresh to an international audience. The signature Australian blurring of good and evil in mass market fantasy is the flavour of the month internationally.

More interesting is the new, less easily defined, cross-genre phenomenon called 'slipstream', which China Miéville recently called the New Weird. Despite the marketing label of 'New', Australians have been happily at work in this genre for decades, most notably in the Tom Rynosseros stories of Terry Dowling. Dowling's is a surreal, fantastical future Australia, neither SF nor fantasy, but blending both with a sense of the mythic and the power of the landscape. Dowling's works shows that there are advantages as well as disadvantages to the independent press phenomena and not having to satisfy the commercial needs of multi-national publishers. He has been successful because he wasn't forced to compromise, but the success has been limited by the limitations of independent presses..

While the current prominence of slipstream is a recent phenomenon, the sub-genre itself has been around for decades, often hiding in other genres. The works of Peter Goldsworthy, Janette Turner Hospital and Peter Carey also often fit the definition, although those writers have come from a literary background. What is interesting is that a large amount of the short fiction published in the independent small press magazines and anthologies also fits this slipstream subgenre. Generic fantasy is on the wane in short fiction. Readers, writers, editors and publishers in the independent press field are simply bored. Is there a grass roots trend emerging here?

But in the mass market, publishers are looking for generic fantasy trilogies, and very little else. Some science fiction is published into the techno-thriller market, witness John Birmingham's Weapons of Choice. Some horror, such as Anthony O'Neal's excellent The Lamplighter, in which a gruesome serial killer mystery is played out by the power of an abused young woman's imagination -- is published in the literary genre. Kim Wilkins, who proved that the mass-market horror novel can work in the Australian market place, is now being marketed as paranormal romance.

The short story field is almost totally the preserve of the independent press. Once again, a number of factors are at play. A whole range of new talent, in writing, editing and publishing, is at work: people who have been inspired both by what has been happening overseas in the independent presses, and by their own talent. The inability of mainstream publishers to take risks in what they still see as a minor genre of the derivative pulp mass market industry helps drive the new talent.

#

Later that night, around the campfire, the roo's mate belched and said: "Use some salt and wild lime next time. And please peel them first." She picked cotton from between her teeth. "Or better yet, I'll cook." Her expression softened when she saw her mate's face. "They were delicious though, darling. And thank you for catching, killing and cooking dinner. I'll wash the dishes."

The roo brightened. "I hope they send us some more! And I caught a koala for desert. But it needs a few more minutes --"

"Koala? Again? We're going to end up eating grass at this rate!"

"-- marinating in the brandy."

"Oooh, that sounds nice."

#

A major factor in the independent press arena is new printing technology. Small presses once photocopied their magazines and fanzines, or used a whole range of expensive backyard production techniques whose names have been forgotten. Now we have effective desktop publishing software, print-on-demand technology, and the capability for cost-effective small print runs. We live in a world where anybody with the will and the ambition can have a go at publishing. That is both a strength and drawback -- will, ambition and resources do not equate to talent and experience.

The real publishing experience lies with the established mass market publishers, who have little knowledge of speculative fiction. The talent most often lies with the independent press. It is one of the ironies of the field that the place where the speculative fiction talent and the publishing experience meet is most often overseas. That is changing.

Where to for Australian speculative fiction? The independent press phenomena will continue. The cottage industry publishers will become more experienced and more knowledgeable. The mass market publishers will always be driven by the commercial imperatives of a small marketplace but, hopefully, will also learn enough from grass root trends to allow the genre to develop.

Science fiction, fantasy and horror are literatures of ideas. Science fiction looks into the future, or at what could exist, given what the human races knows or can imagine about the universe. It looks also at different versions of our past and present -- a sub-genre called alternate history. Horror looks at the supernatural, or at particularly disturbing versions of what can exist, given the perversions of human nature, and here horror crosses with the crime genre. Fantasy looks at worlds or subject matter which can't exist, which we acknowledge as impossible. All are literatures of ideas. Australian writers draw on the vast, often unforgiving, landscape we live in, the multicultural nature of the society around us and the lessons we're trying to learn from our history. The best stories feature characters in conflict with the idea, in search of resolution. The best stories provoke, inspire and entertain. You can read the results in these pages.

#

The real invasion, of course, came later. The kangaroo and his partner were driven out of the Sydney basin to haunt the vast interior of the continent, where their descendants can still be found today, bounding through paddocks, slouching in the shade in the desert heat, fighting sheep and cattle for food -- or dead under the wheels of trucks and on the meat racks of supermarkets ...

...or bounding out from behind a tree, machete in one paw, can of beer in the other, shouting "Your money or your life."

#

In 2004, the Australian short fiction market was dominated (again) by independent presses. In researching this anthology, we read every speculative fiction story we could find by Australian residents, published anywhere in the world. Nearly four hundred stories by one hundred and seventy writers. One and a quarter million words of fiction.

The trends are obvious. Internet publishing is up, and flash fiction -- stories under a thousand words in length -- is also disappointingly on the rise. Speculative genre short fiction is at its best when it has the space to consider plot and character as well as idea, and flash fiction rarely does justice to its subject matter.

The most energetic publisher was Ion Newcombe, of the webzine Antipodean SF, which managed a dozen issues, reinventing the tropes and ideas of SF's heyday in the 1960s. Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine also met their publishing schedule with six bi-monthly issues. Australia's longest running SF magazine, Aurealis, managed a single issue. New Western Australian magazine, Borderlands, managed a single issue, as did the Canberra-based Fables and Reflections. The Florida based webzine, Oceans of the Mind, devoted an issue to Australian writers.

The new horror webzine, Shadowed Realms, put out two issues, the second devoted to flash fiction, a trend which will continue with this market. Orb, the best, and the best-looking, of the local SF magazines, produced a single quality issue. The webzine, Ticonderoga Online, put out two issues.

There were fewer anthologies in 2004 than in 2003. Agog! Press produced the third of their annual anthologies, Agog! Smashing Stories, edited by Cat Sparks, and the Canberra Science Fiction Guild produced their third, Encounters, edited by Maxine McArthur and Donna Hanson.

The year also produced three single-author collections. Black Juice, by Margo Lanagan, published by Allen & Unwin, was the stand-out volume of the year, and 'Singing My Sister Down' the outstanding story of the year. Harper Collins published a second volume of erotic fantasy and horror by Tobsha Leaner, Tremble, with a number of strong stories. Altair Australia Books published the story collection, We Would be Heroes, by Robert N Stephenson, and a poetry collection by Kate Forsyth, Radiance.

In addition, Australians placed stories with a number of anthologies, magazines and webzines, from major publishers and independents, around the world.

For details of websites, subscriptions and addresses of all the Australian based publications, please see the Appendix.

If we had produced a Year's Best for 2003, it would have been dominated by horror fiction; 2005 is already shaping up to be the year of the adventure story. 2004? Well, you'll have to read ahead and find out.

--Bill Congreve & Michelle Marquardt, editors May 2005

©2015 Go to top