Stephen King

PICKING THE BONES

The Stand

MISC.

Hearts in Atlantis film review

Picking the Bones

The Stand (1978)

by David Carroll

First Appeared in SKIN#2.6

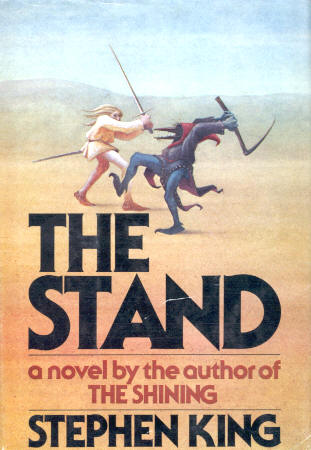

The Stand, Doubleday, 1978: one of my favourite covers |

You can't really, because none of the simplifications hold water, everything has to be compromised somehow. We can say it is Stephen King's most popular book, and he started writing it in Boulder, Colorado out of what was to be a fictionalised account of the Patty Hearst story, and that the original manuscript was large enough for Doubleday's accounting department to suggest cutting it back some -- at least according to the preface of the 1990 'uncut' edition. It was also his last book with Doubleday until Pet Sematary, but that's another story.

Unlike his previous work, and most of his subsequent work as well, The Stand is a large-scale epic in both scope and theme. Not content with tearing apart a family or a town, his destroys America (and by extrapolation, the world) and then stirs through the ashes to see what rises to the top. What does is a very Old Testament style Christianity of trial and sacrifice, and a message about the affirming power of man, and the destroying power of his society.

Fair enough. The actual action and resolution takes place on a much smaller scale, as it must, but an enormous amount of space is covered, and an enormous amount of detail as well. Once again it is plain common sense that brings home the causes and effects of catastrophe -- end-of-the-world scenarios are common, but I believe nobody before King wondered about the effect of all those dead bodies, let alone burst appendices. American ideals are discarded, the establishment is impotent. The Military tries to fix the problem it created, only more empty power-play, and then just fades away, leaving only their toys. A lot of things just fade away, the unknowing masses among them.

Like in 'Salem's Lot, the protagonists of this drama are King's all-knowing heroes, who between them can discuss all matters from fixing power stations to sociological theory, who are not perfect but know what they are fighting for, and why. We are told the masses are there, that the jails will need to return when enough people reach the Free Zone, but we don't really see them. Likewise we don't really see the opposite numbers making up the Las Vegas army, just the Walken' Dude himself.

I stress this is not a bad thing. The story is epic, its characters equally so. Douglas Winter points out the only two real protagonists are Stu Redman and Larry Underwood, the one who follows the action from beginning to end, and the one who must cleanse himself before being fit to be the final sacrifice.

We can start putting all the characters into such categories. Nick is the saviour-figure, Fran is there to bear children (and provoke the rivalry between Stu and Harold), Nadine is there to be temptation and Harold is the author surrogate from Hell. But The Stand is never that simple.

I generally like Stephen King's sexual politics. They seem honest for the characters and situations he writes, and honesty is the best policy. But King has acknowledged the trouble his had with his female characters, and the large canvas of this particular novel only accentuates that trouble, along with a related one. In the battle for world supremacy, where is the non-male-WASP-working-class population? Nowhere really. The flu got them, or Flagg did (along with all the Techies), or relegated them to being vessels for conflict and future metaphor. It takes more than a black female figurehead to dispel that feeling.

In a sense it doesn't matter (I say as I barricade myself in my room) because this is King's tale. It is not the real world, or the real America, but a reflection through an author's eyes, and a perceptive, media-conscious one at that. It depends what you ask of your fiction, and how you read it. All I ask (to keep my own interest, rather than any criteria for what should or should not be) is for it to be true to its characters, and Stephen King delivers.

Frannie Goldsmith is more than just a vessel, and through her diary becomes perhaps the only female example of King's all-knowing hero. Abigail is not a figurehead, and it is more than a little ambivalent what Nick's role actually is, but that's fine. Nadine never really got a choice, and so are her final actions simply a result of being a pawn to one side and then the other, or does she start to take control of what is left of her life, as it seems to me. And then there is Lloyd Henreid, who chooses to stay with Flagg of his own free will. And one thing common to all those characters and a lot more, is that their stories are not glossed over, but told in full. Nick and Larry (and, of course, Randall Flagg, 'why else could he suddenly do magic?') I would like to single out especially for some fantastic exploration of background.

Regarding the subsequent versions of the story, I found the expanded version added less than I expected to that detail but, strangely enough, Mick Garris' 1994 mini-series manages to capture a lot of it in short-hand. Sadly deficient of a lot of the book's power, it does have the scope, and also happens to be an eminently watchable six hours of television. And little moments (Larry wiping his lips after kissing his mother) bring home the characters.

In Danse Macabre King said he actively hated The Stand at times, but never stopped writing it, and George Beahm notes that the first draft drained all the author's creativity for some time. The book works because it is huge and sprawling, and small and intimate. Perhaps it doesn't quite work in the transition between the two. But it's not that simple.

©2011 Go to top